A quick word of introduction. My name is Stuart McDonald and this is Couchfish—the perfect tub of ice-cream for the traveller stranded on the couch. The newsletter has both a paid edition which traces a fantasy itinerary through Southeast Asia, and a free one that covers, well, everything else. You’re reading a mix of the two here today, and if you’d like to read the full edition, you can upgrade your subscription via the button below. Thanks!

In survey after survey after survey, travellers state that they want to travel in a more responsible manner. They want clear information that will help them to choose businesses that support the goals of sustainable tourism. They want, in essence, to do their part to make travel better. Not only better for themselves, but better for destinations and the people who live there, and indeed better for the planet. Laudable stuff.

This is not a new desire. One can’t throw a satay stick without hitting some news story detailing the latest ravages of tourism, and it is heartening that an increasing number of travellers are at least saying that this is a priority for them.

So who should step in and declare “we can fill this sustainability information black hole?”

Cambodia’s Sihanoukville never fails to deliver when I need a “Tourism WTAF photo”. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Booking Holdings, the parent of Online Travel Agents Booking1 and Agoda (among other firms), claims to be “the world’s leading provider of online travel & related services.” According to its own propaganda, as of 2022 the undertaking listed over 28 million places to stay sourced from over 220 countries2. In that same year, the site processed a staggering 900 million room nights worth over US$120 billion.

Who better to have in the steering house of divining which properties are “sustainable”, than a company with a vested interest in recommending as many as possible?

In five acts, I’m going to cover first the genesis of their sustainability platform, how it works, some of the problems with it, consider why we’re seeing these problems, and then look at why this is bad for both travellers and destination residents. About half the post is free-to-read, to read the whole piece, please consider becoming a paying Couchfish subscriber. Membership costs US$7 per month and delivers access to an archive of hundreds upon hundreds of posts. Changed my mind on this—the whole piece is free to read, though if you want to become a paid subscriber, please do!

I. How To Build A Hen House

Sustainable tourism sits upon a three-pronged foundation—economic, environmental, and social. If a business takes a sustainable approach to its undertakings, it takes these aspects and considers how to operate without impinging on the future viability of a destination.

More royalty always makes things better. Pigeon at Phimai, Thailand. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

In considering how to fashion this foundation, Booking turned to Travalyst, another corporate entity founded by some royal dude. The Travalyst mission statement reads:

“Our mission is to make the travel industry more sustainable. We do this by convening leading industry players in a pre-competitive coalition to collaborate on bringing consistent sustainability information to the mainstream for the first time. This means we can empower consumers to make better choices: for themselves, and for the planet.”

As far as I can make out3, Travalyst consulted with the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC)4, an Independent Advisory Group5, and their Accommodation Working Group6. A notable missing wheel is any form of non-tourism stakeholder voice from destinations—this not giving destinations their fair number of seats at the table is a problem that has plagued tourism forever. This ever-familiar oversight aside, this entourage banged their heads together and came up with five areas of sustainability, each with a subset of related aspects. The five areas, followed by their number of subsets, are:

Energy (19)

Waste (14)

Water (7)

Biodiversity & Ecosystems (10)

Destination & Community (11)

The list is, for what it is, sensible—there’s nothing on it that people wouldn’t consider to be a positive step, albeit perhaps the smallest of bandaids in some cases. I couldn’t find the list anywhere on Booking, which is a bit frustrating as properties often list sustainability achievements that are not on the list, so it isn’t clear where some of the benchmarks are coming from. You can see the full list on Travalyst here.

As I mentioned up top, the broad pillars of sustainability are economic, environment and social. While the Travalyst list doesn’t tightly correspond to these, broad strokes the first four fall under environment and the last one, social. Some aspects within energy, waste, and water, have economic angles, but it struck me as curious to not have a top line category for economic impacts. More generally, there are many, many … many, problems with the list—I’ll return to both this omission and the list’s problems later. And while I know this is rich coming from me, Travalyst needs to prioritise the hiring of an editor competent in the English language7.

II. Fill The House With Hens

List done and dusted, participating properties self-select which sustainable practices they’ve adopted within the Booking extranet. I was unable to see exactly how this works, but according to this page, it sounds like properties tick the boxes that apply to them, and this then populates a list on their property page on Booking.

My son Will having a thrilling time in East Java. The homestay we stayed at does not participate in Booking’s scheme—and don’t need to—but will it be bad for their business if they don’t? Photo: Stuart McDonald.

There is also scope to add a property’s various “green” accreditations and certifications etcetera, which can supposedly play a part in checking the accuracy of what properties say, but, as I’ve written before, large tracts of that particular ecosystem more resemble a pyramid or pay-to-play scheme than anything intended to better inform travellers, so I’m ignoring it here.

Tick box ticked, based on the property’s location and practices, the programme’s “eligibility criteria model” (whatever that is) calculates an “overall impact score.” So what does this score look like? Booking has four implicit levels and one implied:

Level 1: “You’ve implemented some impactful sustainability practices.”

Level 2: “You’ve made considerable investments and efforts to implement impactful sustainability practices.”

Level 3: “You’ve made large investments and efforts to implement impactful sustainability practices.”

Level 3+: “This property has made significant commitments towards sustainability by subscribing to one or more third-party sustainability certifications.”

Non-participating.

Levels one to four get a non-clickable stylised leaf icon displayed near the top of their property profile page on Booking. Then, depending on how many price brackets the property has listed—so anything from four to ten scrolls down—after the room pricing, there’s a short section noting the property’s “Travel Sustainable” level with a small link to read more. Click on that and you get a popup detailing what the property is doing. Depending on the property, this popup carries with it a footnote saying either:

“Independent organizations verify all third-party certifications and sustainability steps.”

or, the seemingly more common:

“We’ve begun exploring verification processes for these steps using guests’ feedback and a trusted third-party auditor. However, as of now, we can’t fully guarantee the accuracy of this information.”

Both are followed by a link titled “Learn more here,” which links to the Booking sustainability homepage—good luck learning anything about this there.

On some location pages, Booking offers readers the ability to filter by these criteria—and credit where due, this functionality and visibility has been drastically improved in recent times. However, this filtering is not displayed consistently. For example, if you look at their page for Lamai Beach on Ko Samui, there is no filter nor are any sustainability leafs shown for properties. This seems odd as this is the page you would land on if you were to Google “Lamai Beach Booking”. The leaf (and the filter) often only appear after you enter your desired stay dates.

Without getting too tangled in the weeds, the point I’m trying to make is that for a traveller concerned about sustainable travel, a filter like this, where one can, with a single click, surface only the properties meeting say “Travel Sustainable Level 3,” is super useful, and for properties qualifying for this level, I’m pretty comfortable in guessing it is driving bookings. Indeed, Booking claim that “73 per cent of guests are more likely to book at a property that has sustainability practices in place.” On a quick search for Ko Samui, some 240 of a supposed 599 available properties had at least Level 1.

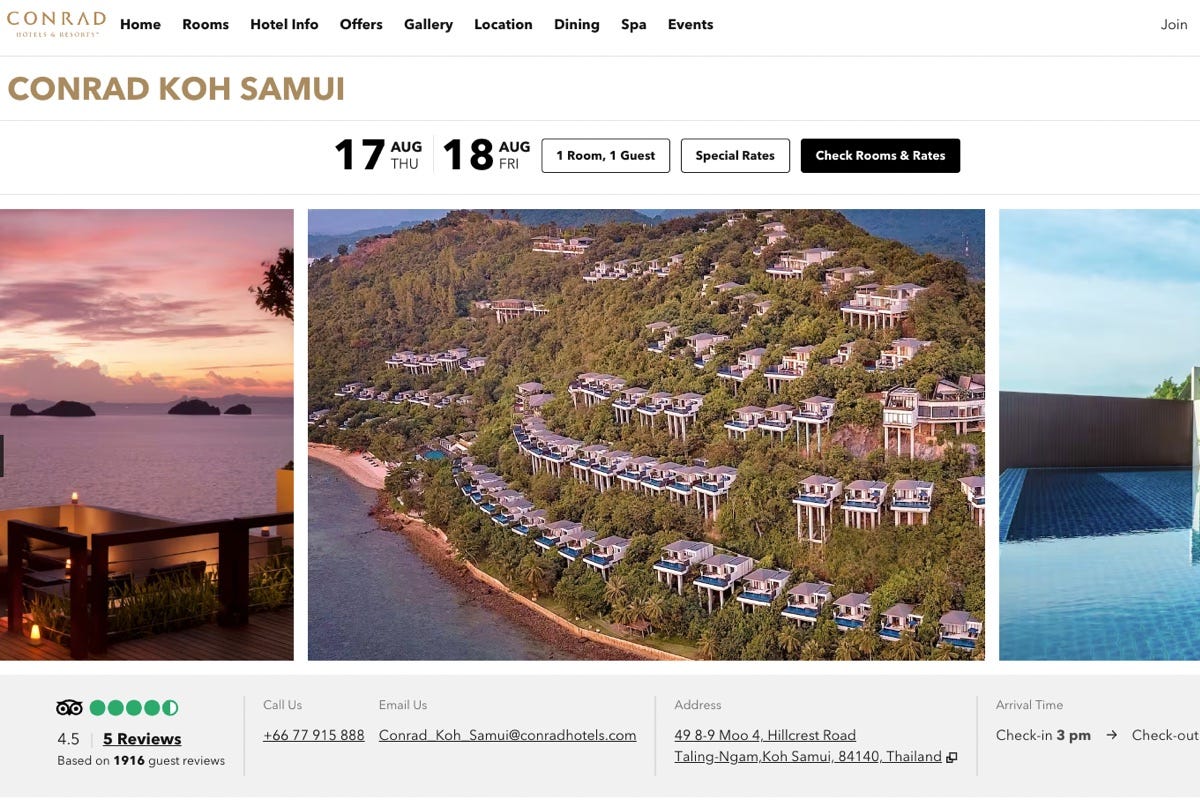

Getting from Level 1 to Level 3 need not be all that demanding. Consider the KB Beach Club and Pool Villas—this is actually the top recommended property for Ko Samui that Booking surfaced to me. It has Travel Sustainable Level 1, and of the 61 items on the Travalyst list, has ticked 18 of them. The Conrad Koh Samui, a Travel Sustainable Level 3+ property, ticks 25 of them. I think (guessing here) the + is related to its certifications. The Conrad’s other extra efforts according to the Travalyst list?

Single-use shampoo, conditioner, and body wash bottles not used

Single-use plastic stirrers not used

Single-use plastic straws not used

Water-efficient showers

Invests a percentage of revenue back into community projects or sustainability projects

Local artists are offered a platform to display their talents

Most food provided is organic

This doesn’t strike me as the heaviest of lifting to jump two levels. I’ll return to the Conrad a bit further along in this piece.

But how useful—and true—is any of this information?

III. Unlock The Gate

Booking are upfront—well, as upfront as you can be when it is via a footnote on a popup reached via a small link some four to ten scrolls down—in saying that they have no idea if the information they use to determine the travel sustainable level is accurate. Indeed, browse hotels in Vietnam and be amazed at just how many of them are 100 per cent renewable energy powered.

If only they could plug me in to some more damn hotels. Wind farm, Phan Rang-Tháp Chàm, Vietnam. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Problems around places making stuff up is hardly breaking news, and Booking does say that properties telling tall tales will have their listings adjusted, but, to my mind, this is only half the problem. The real problem is that the list is, well, kinda shit.

I know I said up top that there was nothing on the list that people would quibble about, but give it a closer read, and you might start thinking this is the sort of checklist you come up with to make it look like you’re doing something when you’re not.

Consider the 100% renewable energy example I used above. By Southeast Asian standards, Vietnam does have a fair amount of renewable—mostly hydro— energy on tap, but it is far from 100 per cent. The chances of a ten-story 3-star hotel in Hanoi being on 100 per cent renewable power is as likely as finding a good bowl of phở in Bali. More to the point, while renewable energy is something worth striving for, I think what is really missing here is context. Let me explain.

Consider a traveller who decides they want to stay at a hotel that takes a prudent approach to its power usage. Telling the traveller a hotel uses 100 per cent renewable power, or that it reduced its use by five per cent over the past year (another tick factor), are both useful to a point. However, as they lack context, as a point of comparison to any other hotel they are largely meaningless.

The real question, is how much actual power does the property use? This matters not only with regard to comparing to other properties, but also to the destination as a whole—how much additional load onto the grid is yet another hotel adding? If you have two hotels, one of which is using the equivalent of the average daily household use per room night, and another is using tenfold that, then that is actionable intelligence.

Booking could require properties to upload their meter readings, from where a per room night figure could be derived and then displayed to consumers. If they wanted to be less explicit, they could develop a bracketed by room night kWh range, say low, medium, and high—with specific figures—and then note what the average per-capita power use is for the country concerned. This is much more useful information from a concerned travellers’ point of view.

Water use, as I’ve written before, is another great example. The Ritz Carlton Langkawi uses 5,387.51 litres per room per night while the average daily household use in Malaysia is 191 litres. On Booking, the Ritz Carlton Langkawi has Travel Sustainable Level 3—the second highest level of sustainability Booking awards. The Ritz Carlton on Ko Samui—an island dealing with a major water crisis—uses 1,467.75 litres per room night, and on Booking is again a Travel Sustainable Level 3 property. Meanwhile, Ko Samui requires 30,000 cubic metres of water per day—24,000 of which is piped in from the mainland.

When a destination is having a water crisis, this is the sorta joint I’d want to be staying at. Also, a Travel Sustainable Level 3+ property. Seems solid. Screenshot from the Conrad website.

Hard numbers help. As I’ve written before, when the Banyan Tree Group states that “Over 2,100 km of cling film has been reduced, almost the equivalent distance from Singapore to Manila,” the real question is holy hell, how much are you still using?

On the people side of things, again and again and again the term “local” emerges. What do they mean by local? A local citizen or a foreigner living locally? I’ve highlighted this as being problematic with tour companies in the past. Saying 80 per cent of staff need to be “local” (a tick item) means nothing if management form five per cent of the staff—and they’re all foreign. If a foreign manager lives locally (as most do), are they local?

As I’ve written before, economic leakages—where money leaks out of the local economy—form one of tourism’s many bugbears. A study of hotels in Bali, Indonesia found that luxury chain hotels can have a leakage rate north of 50 per cent, while homestays score below ten per cent. The biggest source of leakages were F&B followed by staff and management fees. Why is this not presented in a simple fashion on Booking’s sustainability checklist?

In all these examples, there are hard numbers available from properties. What does their power meter read? How much water do they use? What is the nationality (not residential) breakdown of staff? Where is the money going?

IV. Call In The Foxes

It is with this last question—where’s the money—that the biggest questions arise. As a part of researching this story, I went to set up a fake property on Booking to find out what commission was applied. To be clear, I stopped short when I had to tick a box saying the property was legitimate—so sadly you will not be able to book a room at Skye Govinda Lodge in Bali. Skye Govinda, in case you’re wondering, is the name of my dog.

Skye is not really selling her lodge well. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

The out-of-the-gates commission rate was 17.3 per cent. This can increase if you want Booking to charge cards for you (an additional three per cent), and there are apparently a raft of other additional commissions you can pay for stuff like improved visibility on the site—a practice that has garnered legal attention in the past.

This commission though, is a direct economic leakage. Why isn’t the commission a property pays to Booking (or Agoda, Expedia, Google, or whoever), listed? Why doesn’t Booking list, for each property, the country it pays the room fees to? If you book a hotel in Bali, and Booking pays your money into the hotel’s parent company bank account in Canada, how much of that money makes it to Indonesia? Yes, the Canada bit is a joke, what sensible hotel company wouldn’t do all their banking in a tax haven? Best of all, Booking already has this banking information, and knows it is correct. They could put it up on the site yesterday.

Luxurious hotels are prone to economic leakages, and use considerably more water and power than small homestays. The latter can provide important support to poverty alleviation in destinations, but the former, well their potential is more towards supporting the bottom line of Booking (or any online travel agent). Let’s return to the Conrad Koh Samui—a hotel with somewhere between 50 and almost 100 private pool villas8—where rates start at US$485 a night. Being generous and assuming they’re on the baseline 17.3 per cent commission, a night booked there would net Booking over $80. At my fictional Bali doggie abode (no doggie horizon pool sorry), where a double room costs 295,000 rupiah (roughly US$19), the commission comes in at around $3.

V. And Look The Other Way

Is it in the interests of travellers and destinations to have a company that profits off of every room sold, play a central role in the design of a platform to showcase the sustainability efforts of said properties?

Whose interest does it serve to have a sustainability checklist that pointedly ignores the highest impact practices of the most impactful style of property?

Of the 14 waste categories, eight relate to single use plastic. Seriously? Let me simplify this for you Booking—does the place of business use single use plastic? Yes or no. Why are businesses gaining up to eight ticks over single use plastic, while not even being asked where they do their banking? Why are there separate ticks for bicycle rental and bicycle parking? I mean, how do you rent them if you have nowhere to park them?

A real distraction. Lembata, Indonesia. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

These are all a distraction. They’re the low-hanging fruit that any business in their right mind should be doing anyway. A property doesn’t need a sustainability consultant to tell them to switch to refillable water, or compost, or sort their trash—they need a decent accountant. I’m not saying single use plastic isn’t a problem—it most certainly is. What I am saying is that if Booking was serious about single use plastic they could come out and say something like:

“From January 1, 2024, if your property uses single use plastic, you cannot be listed on Booking.”

Now that would be a statement—and one that brings me to my final point in this never-ending post.

Why is Booking’s approach all carrot and no stick? By all means give eights ticks for plastic but why not deduct points for soaking up ridiculous amounts of water and power, or ignoring local laws about building one hundred metres back from the high tide mark? As matters stand, a hotel can continue with all manner of damaging business practices, and yet retain a Travel Sustainable Level 3 ranking.

It is in Booking’s financial interests to have as many properties listed at Level 3 as possible and none of this is about “empowering consumers to make better choices: for themselves, and for the planet,” rather it is about rendering the concepts behind sustainable travel even more meaningless than they already are, while minimising any financial downside and keeping travellers booking—on Booking.

We have an organisation that has processed over US$120 billion in bookings—in many cases channelling that money to the least sustainable properties of the entire industry—in the planet’s tourism sustainability wheelhouse.

And that isn’t good for anyone.

Update: I received some feedback suggesting I had been unfair in not soliciting comment from Booking or Travalyst. This is not correct, I did email both firms, but didn’t hear back from either—but I forgot to mention this in the post—sorry and thanks again for the feedback!

Couchfish is 100 per cent independent and reader-supported. If you’re not already a subscriber, and you’d like to show your support, become a paying subscriber today for just US$7 per month—you can find out more about Couchfish here—or simply share this story with a friend.

Don’t forget, you can find the free podcasts on Apple, Pocket Casts and Spotify as well as right here on Couchfish.

In the past Travelfish worked with Booking on an affiliate basis, but that agreement and working relationship was terminated in (I think) 2017. I’ve done some copywriting for them since then, but again that is no longer happening. Travelfish does work with Agoda and Rental Cars (both companies owned by the same parent) on an affiliate basis.

While Booking claims a reach of 220 countries, according to Wikipedia there are 195 countries and dependencies on the planet, so we’re not off to a great start here. What is it with country counters? They are just intolerable.

According to this page, the programme was both developed and verified by unnamed independent industry bodies and Travalyst—as the latter was the only one named, that is who I’ve looked at in this story.

The 2007-formed GSTC is an ostensibly not-for-profit US-based non-governmental organisation, involved in sustainability in tourism, and certification related to it.

The Independent Advisory Group is a who’s who of smart-cookies, well respected in the field of tourism sustainability. Many are academics—including Dr. Susanne Becken, Dr. Xavier Font, and Professor Paul Peeters—all whose stuff I’ve been poring over for my Masters, thank you all!

I couldn’t find a list of who makes up the Accommodation Working Group, but I would assume it’s the usual suspects listed all over the Travalyst website—Booking, Expedia, Google, Skyscanner etcetera.

“Properties electricity is 100% renewable,” “Property has reduced energy consumption this year with at least 5% compared to previous year,” “Property has drought-tolerant landscaping with reduces irrigation needs and water use,” etcetera. These are all from the Travalyst list—petty I know, but jeez, come on fellas.

While I couldn’t find an actual number on Booking—nor on the Conrad site—according to Agoda it has 66 private pool villas, while TripAdvisor says it has 88.

Share this post