People often say “if only we’d known then what we know now,” and so it was the other day, when I stumbled upon a 2006 Overseas Development Institute working paper by Caroline Ashley. Titled “Participation by the poor in Luang Prabang tourism economy: Current earnings and opportunities for expansion” it shows that people did know. If you’ve ever wondered just where your money goes, you should read it. It is dated—16 years is a long time—and there are a few typos, but regardless, it provides a valuable snapshot of Luang Prabang and plenty of insight worth considering for travellers who believe their travels should actively work to help those most in need.

The year is 2006 and Luang Prabang has been at the pinnacle of the nation’s “must see” list for at least a decade. In 2000 there were 65,225 international arrivals—a number that would rise to 133,569 in 2005, and which, by 2019, would skyrocket to 860,035. For a country with stubbornly high—and persistent—poverty levels, can tourism help?

Everything in Luang Prabang is photogenic. Photo: Cindy Fan.

The working paper’s executive summary does a good job of, well, summarising:

“This report explores the workings of the tourism economy of Luang Prabang from a pro-poor perspective. It makes rough estimates of where tourist expenditure goes, and where poor and poorish people are earning incomes from tourism. It assesses four sub-chains of the tourism value chain: accommodation, food and drink, handicrafts, and excursions. The estimates of expenditure and income are extremely rough. Nevertheless, they paint a picture of where money is flowing in the tourism economy.”

According to the report, at least US$6 million flowed to semi- and un-skilled people in Luang Prabang in one year. This represented around 27% of the total tourism receipts of about $22.5m. Food and drink earned the lions’ share (over half), followed by crafts.

So what was a typical tourist in Luang Prabang in 2006 like? About 72% were from the West, with Europeans making up 50% of the total. Asian visitors made up the other 28%, the majority of whom were Thai. Around half flew in (half on international flights, the other half on domestic), the other half by boat or bus. The majority of tourists were independent travellers. Package groups were over-represented at the top end.

Laters of pretty. Photo: Cindy Fan.

The report goes on to say:

“The majority of tourists in Luang Prabang are backpackers who are travelling for several weeks or months. They stay in budget accommodation, eat local food, drink beer, buy curios that are light, and arrange their own local transport and trips. They are generally under 40. The up-market tourists are quite different: their hotels or guesthouses cost ten to 30 times as much, they fly in and out, they are more likely to book through travel agents and tour operators and go on organised excursions.”

The average stay was around five days, and while most stayed around three days, a minority stayed far longer. While budget travellers accounted for 58% of the market, they accounted for 68% of the bed nights. At the time, Luang Prabang had 17 hotels and these were often family-owned though some had a foreign hand. Women owned only a third. Meanwhile, there were 131 guesthouses, with an average of ten rooms apiece. Virtually all were family-run local businesses and most had women as the registered owner.

Pay more, get more. Photo: Cindy Fan.

Where it gets interesting with accommodation is with regard to where the money went. According to the report, the total tourist spend on accommodation was $8.6m. The amount that went in wages and benefits? Around $550,000—six percent. Here, the upper end hotels paid more and used more staff—roughly 1.3 per room versus 0.3 in a guesthouse, but despite this, as a percentage of revenue, their labour costs were below average—five percent. The guesthouses? They were more likely to hire family members and semi- or un-skilled staff. Anyone who stayed at a guesthouse in Luang Prabang in the 2000s would back this statement up.

While guesthouse staff levels were lower, these workers lacked the skills for a hotel job. This is another point the report emphasises—a need for more training. It notes that at the time training was adhoc, with plenty of scope for improvement.

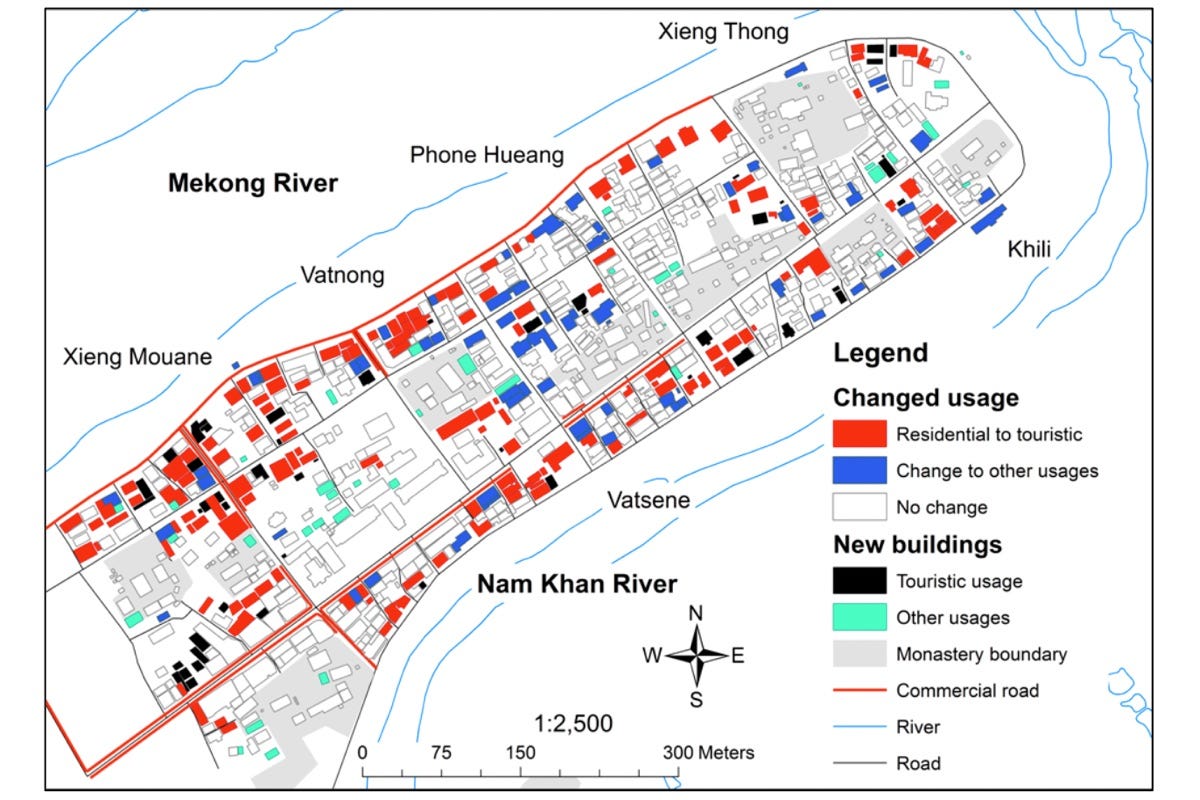

Another factor to consider is how accommodation was changing the town. According to Analysis of the Changing Landscape of a World Heritage Site: Case of Luang Prabang, Lao PDR, between 1999 and 2009 there were big changes as demand ramped up. Looking at conversions from residential houses versus new builds, 78 residences became guesthouses while 24 were in new buildings. In comparison, 14 hotels were residential conversions while seven were in new buildings. Guesthouses dominate conversions as they required less capital and were less regulated. In total 141 conversions took place and the image below puts the transition in context.

Red marks a decade of change, from 1999 to 2009. Source: Analysis of the Changing Landscape of a World Heritage Site: Case of Luang Prabang, Lao PDR, page 8.

On the food side, Luang Prabang had an incredible 1,242 restaurants. The majority of these were family-run, offering 10-30 tables and meals at around the $5 mark. Foreign-owned (often French) restaurants were in the minority. The playing field in this regard could not be more different today—at least there is no Starbucks.

The report estimated that in one year tourists ate over one million meals in Luang Prabang and spent about $7m. Of this $7m, about half went to producers of Lao meat, veges, fruit, rice and so on. This was the biggest single financial flow into the local economy. A raft of suggestions were made about building on this, including import substitution, smoothing connections between hotel food buyers and the producers, showcasing more Lao food on menus, and, of course, there’s a whole section on seaweed. In case you are wondering, in 2006, a Western traveller drank on average one beer per day—I was surprised it was this low to be honest.

With shopping, the report took a detailed look at textiles, where tourists spent $3m in the year. A large proportion of the workers were women and a minority from ethnic minorities. Of this spend, some $1.1m ended up with local producers, vendors and workers. Upmarket tourists spent about three times as much as backpackers on souvenirs. I guess in part, because they didn’t have to carry the the bloody things on their backs for the next three months. The report highlights the night and day markets as excellent approaches. Product diversification and higher value goods are also earmarked as desirable. Both changes have taken place.

You will need to buy another backpack. Photo: Cindy Fan.

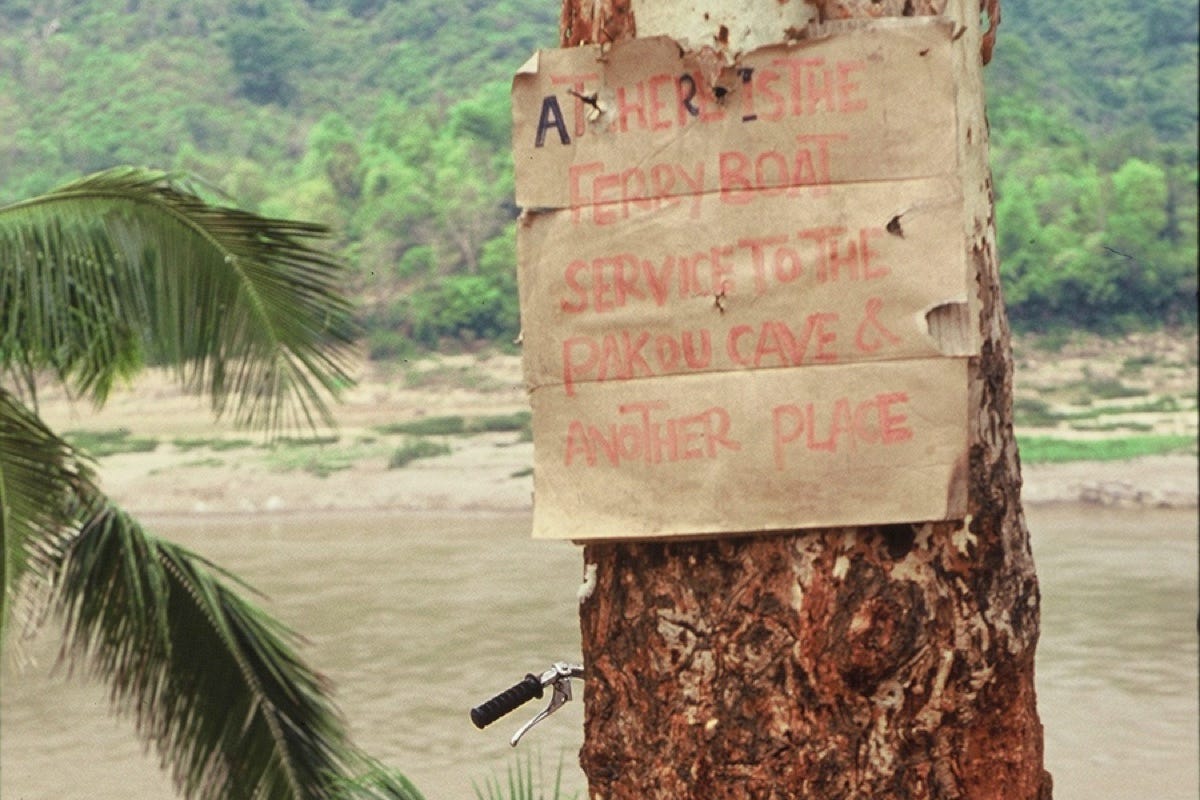

On transport, for day trips and so on, the difference in village participation was stark. Some integrated themselves well—if bizarrely—but most left plenty on the table. The report highlights selling food and drink—the simplest of actions—as being an easy step. Excepting Muang Ngoi, which is a destination in its own right, overnight stays didn’t move the needle. Why? One reason was many don’t have the time.

You need to be in Luang Prabang for a while to have the luxury of contemplating a series of day trips or an overnight one. An obvious step would be to mandate that tour groups must stay long enough to allow something like this to happen. It is though, a hard sell. From tour operators I have spoken to for another piece in this series, by day two or three, clients’ feet are itching. “They [the pax] don’t need five days or a week to tick a box,” was how one put it.

Take me to another place. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

So what did people spend back then? Budget travellers spent $20 to $30 a day and $118 per trip, while high-end tourists spent $100 or over per day and $344 per trip. For the former, food was the biggest expense, while for the latter it was, by far, accommodation. That accommodation, if booked through an online agent, immediately offshored some revenue. How much? Anything from ten to fifty percent—or more. That might not feel so onerous when you’re paying $10 a night, but at $300 a night, it is a significant loss for the destination—and the hotel! [This OTA commission stuff is me talking—it wasn’t covered in much depth in the report.]

Per trip, semi- and un-skilled people earned about $35 for each budget traveller and $59 for an upmarket one. This suggests the latter are better, but roughly 30% of a backpacker’s spend accrued to the semi and un-skilled while only 17% of an upmarket tourist’s did.

So what am I doing writing about what a working paper reported back in 2006—some 16 years ago? For starters, this is the most detailed report I’ve seen that looks at where peoples’ money goes in a specific destination in Southeast Asia. I found the report to be very interesting and I encourage you to read it if you’ve the time. Clearly some others have, as over the 16 years since, many of the changes recommended in the report have seen the light of day. At least to some degree anyway. This is good.

Get out on the river before they dam the whole thing. Photo: Cindy Fan.

I’m also writing about it because as per the report, independent travellers were important. Yes, it was a mixed bag, the conversion of residential properties in particular is a problem. That said, a greater share of independent travellers’ money reaches the semi- and un-skilled than any other. If you feel that tourism can have a role to play in poverty alleviation, this matters.

I’m also writing about it because to some degree every town in Southeast Asia is its own Luang Prabang. For government talking heads to do their upmost to deter independent travellers is both damaging to their very own people, and just plain dumb.

Other episodes in the Rethinking Tourism series:

National Chocolate Milk Day (World Tourism Day)

Nice Tourism (Sustainable Tourism)

The Benevolent Lie (Responsible Tourism)

The Year Is 2006. The Town Is Luang Prabang (Pro-poor Tourism)

Zoom in to the Red Plastic Chairs (Slow Travel)

The Petro-bourgeoisie (Flying, carbon etcetera)

Reality Check (Tour companies)

Follow the Money (Money matters)

Foundations Matter (Community Based Tourism)

Couchfish is 100 per cent independent and reader-supported. If you’re not already a subscriber, and you’d like to show your support, become a paying subscriber today for just US$7 per month—you can find out more about Couchfish here—or simply share this story with a friend.

Don’t forget, you can find the free podcasts on Apple, Pocket Casts and Spotify as well as right here on Couchfish.

Share this post