A quick word of introduction. My name is Stuart McDonald and this is Couchfish—the perfect tub of ice-cream for the traveller stranded on the couch. The newsletter has both a paid edition which traces a fantasy itinerary through Southeast Asia, and a free one that covers, well, everything else. If you’d like to support me finding more tourism stuff to moan about, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you.

A couple of times a week my son has archery class over in Pererenan, a “village” a little to the west of central Canggu. Taking him there by motorbike grates—in part for the abysmal traffic but also because I loathe Canggu. Tourists riding sans-helmet has always annoyed me—despite it being a footnote as far as tourist idiocies here are concerned. There’s no shortage of such fools in Canggu, but the prevalence of “road is softer in Bali-ites” doesn’t explain why I dislike Canggu.

Where better to prepare for the apocalypse than near Canggu? Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Then the other day, I read the following:

“Having a lot of tourists around can be a nuisance for other place users, but the real challenges emerge when local shops are replaced by tourist outlets selling waffles and Nutella, when the prices of accommodation drive local residents out of city centres and when local culture is replaced by a caricature of itself. This is not just the fault of the tourists, but also depends on the functioning of property markets, local businesses and (the lack of) effective regulation. It is also important to realise that many of the processes linked to tourist gentrification can also operate in the absence of tourism. In many areas increasing property prices and local displacement preceded the arrival of tourists. Tourism has simply enhanced and intensified the process by bringing in more external capital.”

It’s from a far longer—and very interesting—interview with tourism academic Greg Richards over on Tourism’s Horizons. Go read it, I’ll wait.

Incessant development and loons on motorbikes aside, what Richards describes is what bugs me about Canggu. What in particular jumped out at me was this bit:

“...but the real challenges emerge when local shops are replaced by tourist outlets selling waffles and Nutella...”

What is local?

Not before time, there’s been a rash of advisory stories of late, all trying to help travellers spot greenwashing. Right across the travel industry this is a massive issue, and it is great that more awareness raising is underway. These are though, concentrating on only one aspect of the problem—the environmental. What about localwashing?

I have no Canggu short-cut pics hand, but rest assured it is far worse than this (also near Canggu). Photo: Lyla McDonald.

You can’t throw a satay stick without hitting some—often foreign owned—travel startup that is using some take on local as a part of their Unique Selling Point. You can travel with/like/by/through locals, you can eat with/like/by/through locals, you can do a tour with/like/by/through locals. The list is about as long as the—rapidly diminishing—availability of domain names. But what do they mean by local? Good question.

As I wrote a while back, when I questioned G Adventures on their dubious take on “local”, they never bothered to answer. More recently I asked travel planning start-up Elsewhere about what they meant by “local” with the following:

“Let’s call this system what it is - totally unfair. Our direct-to-local model allows 87% of your trip dollars to stay in the destination, empowering its communities with long-term, locally based income.”

For my efforts I got the KLM support treatment, so I have no idea what they do actually mean by this. (If you don’t know why I’m on about KLM, they’re notorious for dealing with legitimate gripes which could be dealt with publicly by diverting them to private messaging, often via Twitter DMs, where they then ignore you forever.)

“Please contact us via DM so we can ignore you forever there.” Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Does it matter?

Once companies are making “local” a centrepiece of their marketing, it absolutely does. So, just as a company should be challenged for claiming their tours are “planet friendly,” likewise on any company running tours (or whatever) being “good for locals”.

But who is a local? What is a locally-owned business. In my personal opinion a local is a citizen of the country. A locally-owned business is one that is majority-owned by said locals. Others disagree, arguing any foreigner resident in the country could be seen as a local. To this I’d ask, well how long need they be a resident? How should “resident” be defined? Should residency be dictated by visa, marital status, or some other benchmark?

It gets messy, fast.

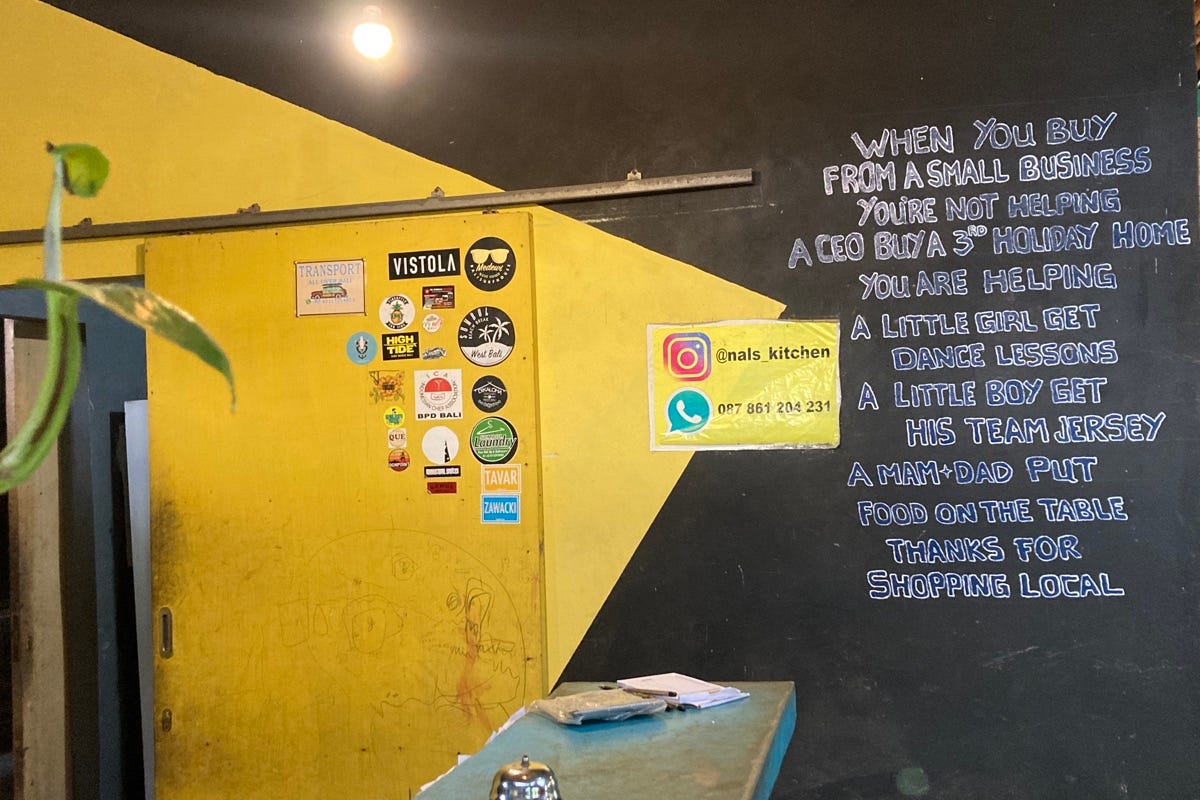

Signage at a Medewi restaurant in West Bali. 10,000% this. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Circling back even to Richards’ statement above and it isn’t all that clear. Does he mean shops owned by locals, or shops selling local goods? If a Swedish dude opened a babi guling joint on the Canggu shortcut—something sorely needed to pass the time while the traffic ebbs—would that be less bad than if he was flogging meatballs?

Just to be clear, I’m not railing here against all foreign businesses. While I agree with the issues Richards’ raises, what concerns me more, and what can be directly tied to tourism, is the blurring by travel companies of what local is. This is the whole “embrace, extend, extinguish” mentality at work, where terms that once held meaning are stripped of it. We’ve seen this happen for decades in tourism, more so now than ever. Who’s up for a responsible cruise holiday to Antartica?

“Sustainability” super-sized. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

As regular readers will know, tourism and sustainability rests on three pillars—economic, environmental, and social. When travellers take their business to locals, you can argue they’re supporting at least two of these pillars. This is why this stuff matters.

Big business however turns this on its head. Consider an example of a foreign tour company that majority-owns the in-country DMC they use. Customers think that they’re supporting local businesses, and in front of the veil, they are. Lift the veil though, and a sometimes significant portion of their money—which they think is staying in local hands—is getting siphoned off to the mother ship. That would be, more often than you might think, a mother ship anchored somewhere warm and tropical—and far away from Southeast Asia.

What’s today’s tax jurisdiction again? Photo: Emma Davidson.

Foreign-owned companies can bring with them all sorts of good. They can bring dosh, talent, connections, and experience by the bucketload—and these all can be agents for good.

The problem is when they start pretending they are what they are not. That’s a bad deal for everyone—except them. Question everything—and skip the Nutella waffles.

Couchfish is 100 per cent independent and reader-supported. If you’re not already a subscriber, and you’d like to show your support, become a paying subscriber today for just US$7 per month—you can find out more about Couchfish here—or simply share this story with a friend.

Don’t forget, you can find the free podcasts on Apple, Pocket Casts and Spotify as well as right here on Couchfish.

Share this post