A quick word of introduction. My name is Stuart McDonald and this is Couchfish—the perfect tub of ice-cream for the traveller stranded on the couch. The newsletter has both a paid edition which traces a fantasy itinerary through Southeast Asia, and a free one that covers, well, everything else. If you’d like to support me finding more tourism stuff to moan about, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you.

After spending New Years of 1941 in Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam, 75 crew boarded the Kaidai-class cruiser submarine I-66 and left port. Along with the crew, were six torpedo tubes, a deck gun, and an anti-aircraft gun. On her second war patrol of World War Two, she was bound for the Bay of Bengal via the Lombok Strait and the Andaman Sea.

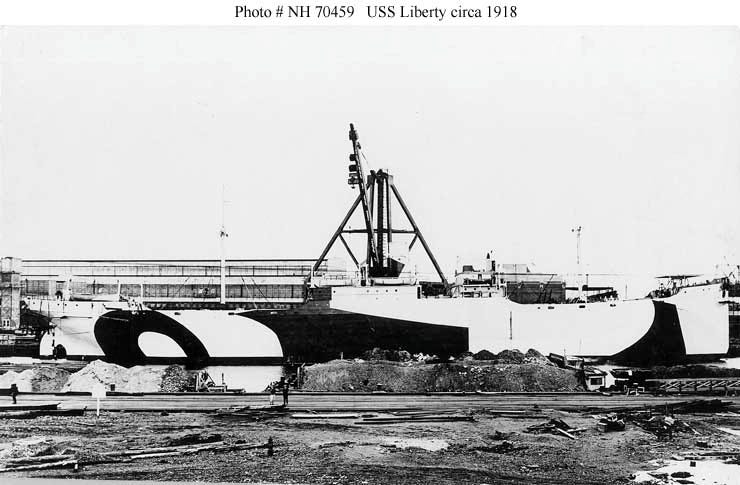

As the I-66 made her way southeast, through the South China Sea, the USAT Liberty, a US-flagged freighter, was heading north. Laden with rubber and railway parts—or explosives, depending on the source—the Liberty was enroute from Australia to the Philippines—or Batavia (Jakarta), again depending on the source. With a displacement of over 13,000 tons and 70 crew, the vessel had but two small deck guns.

The I-65, the same class of submarine as the I-66. Photo: 日本海軍艦艇写真集 潜水艦・潜水母艦p70, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

You know where this is going right?

Before dawn on her sixth day at sea, around 15 km due south of Nusa Penida’s Kelingking Beach, the I-66 sighted the Liberty. She torpedoed it at 04:15, leaving the Liberty dead in the water, then made her escape. Two Allied destroyers—the USS Paul Jones and the Dutch Van Ghent—took the Liberty under tow and steamed for Singaraja on Bali’s northern coast—the primary port of the Dutch colonialists.

With the Liberty crippled, even after they’d cleared the fast moving waters of the Lombok Strait, she continued to take on water—Singaraja was to be a nautical mile too far. Deciding to cut their losses, and hoping to salvage as much of the cargo as possible, they beached the Liberty, and she capsized on Tulamben’s pebble beach on January 14. For the Liberty, the war was over, and once relieved of her cargo, she became yet another coastal rusting skeleton.

The USAT Liberty in better days. Photo: U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Some twenty and a bit years later, in 1963, Bali’s Mount Agung erupted. Windsor P. Booth of National Geographic was on Bali enroute to Sangeh Forest at the time, and later wrote in the September 1963 edition:

“There was a gentle tapping, as of rain, on the roof of our car. Oddly, no drops appeared on the windshield. Then the sky suddenly darkened.

I stepped out of the car to find that the “rain” was volcanic ash mixed with cinders.

No longer was the landscape a joyous rhapsody in green. Now all was bathed in an unearthly saffron light, because ash and clouds had blotted out the sun. Familiar objects, like trees and houses, took on grotesque shapes.”

When colleagues returned two weeks later, they wrote of the devastation, noting:

“By far the worst havoc struck a group of villages due east of Besakih. So sudden and complete was their destruction that even two weeks later officials could not be sure what happened. Many places, cut off by avalanches and lahar flows, were still too hot to be entered. Bodies were buried—or eaten by dogs—where they fell.”

The eruption took place around the greatest of all Balinese rituals, the Ekadasa Rudra. In the very readable Bali A Paradise Created, Adrian Vickers describes it as “the centennial rite of exorcism of the eleven forms of the terrible god.” An exorcism the eruption was, with thousands of lives lost, and vast tracts of land reduced to stony moonscapes.

“Acrid muck, 30 feet deep in spots, buried much of nearby Selat.” Photo: Robert F. Sisson, National Geographic.

While the Nat Geo correspondents kicked around Bali’s south and east, to the lesser-populated reaches along the island’s northeast coast, torrential rain and lava flowed. From Agung’s northern lip a blanket of lava gushed down to the sea, destroying all in its path. At the coast it tumbled over the black round pebbles that give Tulamben its name, and there, with an assist from earthquakes, it cradled the long-forgotten Liberty, and pushed it back out and into the depths one last time.

The wreck lay there, only a couple of dozen metres from the shore, out of sight and out of mind for another fifteen years. Through these years, Bali’s tourism scene grew, and while diving was a thing, its focus was the east coast out from Candi Dasa. It wasn’t till 1978 that an enterprising tourist agent in Denpasar started offering dive packages to visit the wreck. It would be another eight years before a dive centre opened in Tulamben—at the Paradise Hotel.

Baskets before bottles. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

By 2005, Tulamben was on the map, but while attracting almost 8,500 foreign visitors and over 2,000 locals wasn’t nothing, it wasn’t a lot—for Bali. Fast forward another decade though, and the numbers increased to over 65,000 and 7,000 foreigners and locals respectively.

As tourist numbers—and revenue—exploded, tensions rose, but community leaders enacted a customary law that decreed that “every person will have an equal chance to serve visitors.” Through working with and empowering the local community, local people became well-represented in the trade. Training programmes were enacted, and all manner of tasks, wherever possible, drew from local labour sources.

Me and some chunk of the Liberty. Photo: Intrinity Divers.

Unlike some other areas of Bali where foreign divemasters are common, not so much in Tulamben. Indeed some locals, such as the women who carry the oxygen tanks on their head to the dive entry point, became almost an attraction in their own right.

Alongside this, steps were taken to protect the viability of the wreck—essential if divers were to continue to visit—and the undersea environment has thrived. Aside from the wreck itself, artificial reefs have been set up and coral restoration work continues both in and around Tulamben and elsewhere along the coast.

It isn’t perfect by any measure—in season there are too many divers—and too many do touch and damage the coral, but compared to some other diving spots, Tulamben is quite well run. Most importantly, the community management of the site has strengthened the sense of both pride and ownership, and those vested in it understand the potential it holds for future generations.

Nat Geo’s 1963 spread.

Back to the eruption for a moment, Vickers suggests the eruption may have marked the success of the ritual, noting:

“Great state rituals such as this are meant to bring about an age of harmony in the world, but the way they can bring it about is by harnessing and even accelerating the forces of chaos and destruction which precede the renewal of a golden age. In the eyes of many Balinese, the eruption was a manifestation of great change which could bring good results as well as bad.”

It might be a bit of silver linings and all that, but I don’t think Tulamben would be the place it is today, lives changes and all, if the wrecked carcass of the Liberty was still laying on the pebbles.

Couchfish is 100 per cent independent and reader-supported. If you’re not already a subscriber, and you’d like to show your support, become a paying subscriber today for just US$7 per month—you can find out more about Couchfish here—or simply share this story with a friend.

Don’t forget, you can find the free podcasts on Apple, Pocket Casts and Spotify as well as right here on Couchfish.