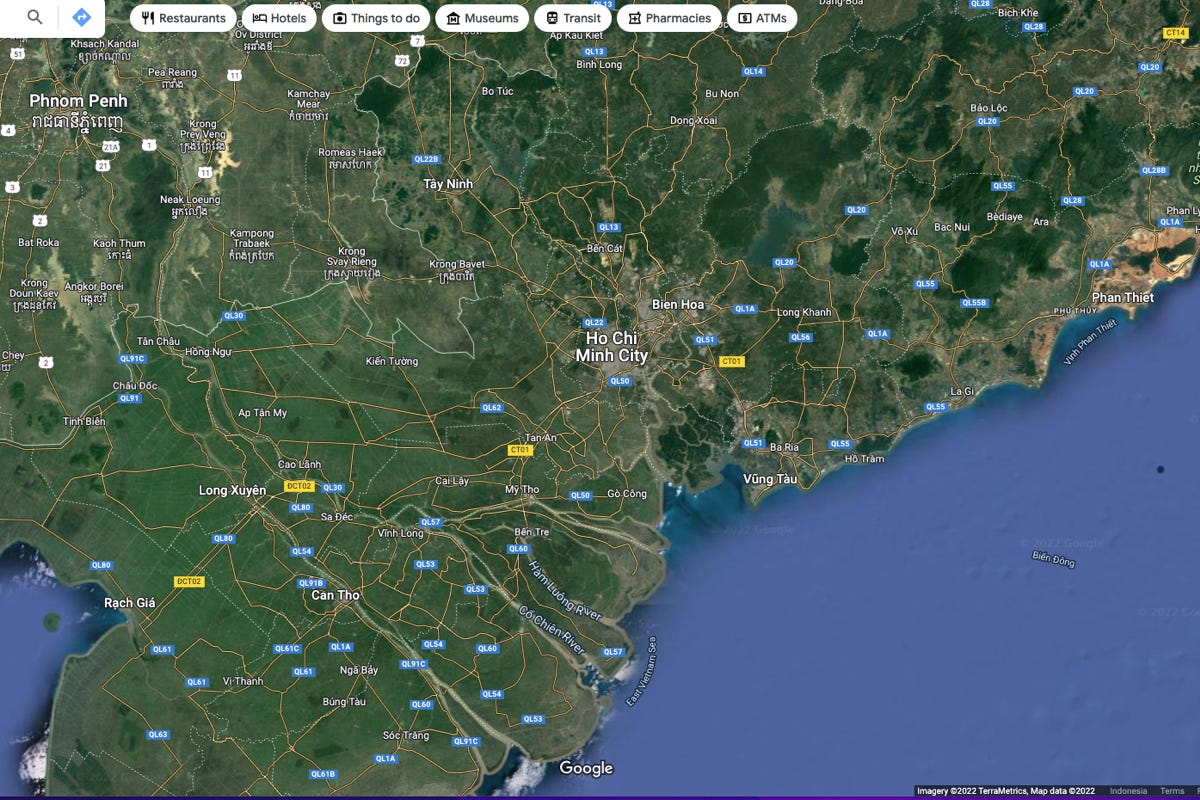

Power up Google Maps and while still zoomed out, centre the map on Ho Chi Minh City, then switch it to satellite view. Click zoom in. Zoom in again. Keep zooming. Pretend you’re at a CIA field station in a new Mission Impossible flick. Watch as the city comes into view. There’s the airport, the undulating river, a still tree-lined boulevard. Keep zooming.

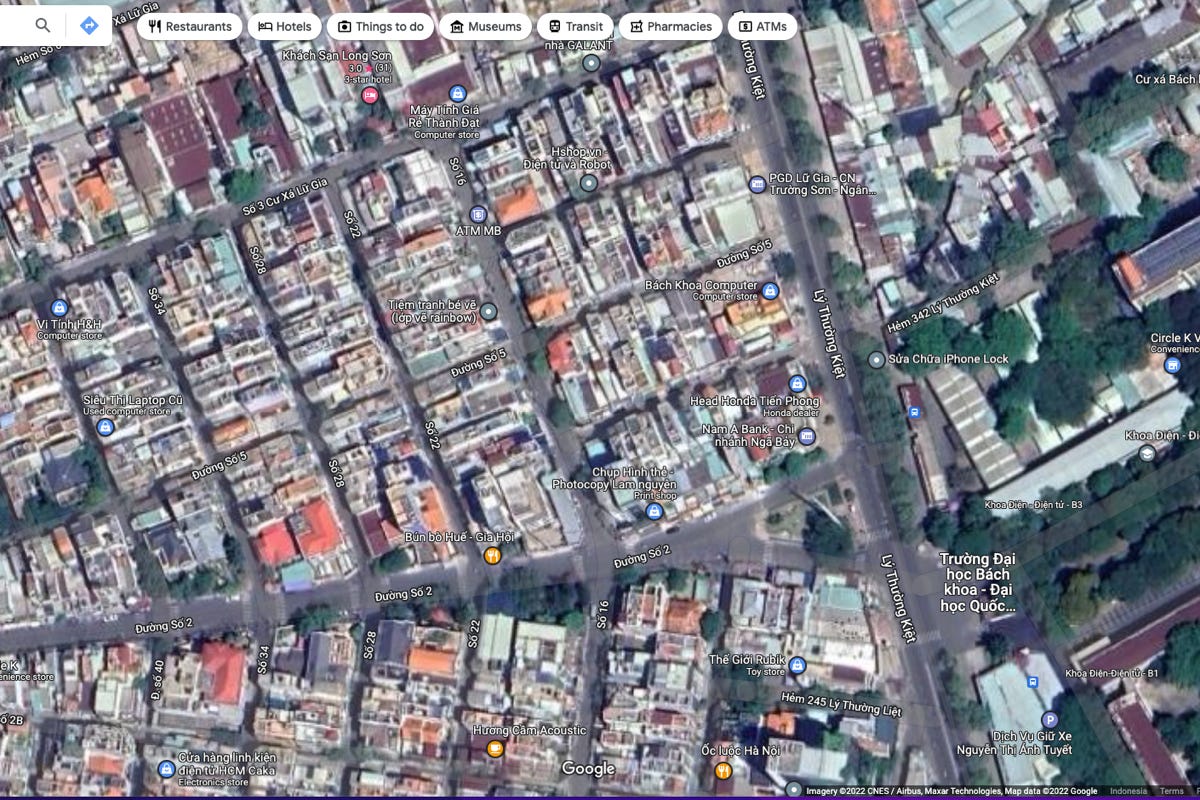

Each click, each zoom, wait till the image loads nice and sharp, then zoom again. Keep zooming until a single city block, it doesn’t matter which, District 10 is good for this, fills the screen. By city block I don’t mean a block of blocks, I mean a block—be careful not to zoom too much. Are you there yet? Has it fully loaded? Can you see the red plastic chairs? Well done.

Start here.

Your mission, should you decide to accept it dear reader, is to head to Ho Chi Minh City and spend an entire day exploring this single block.

There will be plenty of disagreement on this—an increasingly common issue I keep running up against in this series—but, the mission above is a type of slow travel.

Slow travel, as the term is popularised today, is often seen as an offshoot of the slow food movement, but in fact, the concept is as old as travel concepts come. Lucy Lethbridge, in the thoroughly amusing and interesting Tourists: How the British Went Abroad to Find Themselves quotes John Ruskin from The Stones of Venice as he laments the speeding up of travel:

“In the olden days of travelling, now to return no more, in which distance could not be vanquished without toil, but in which that toil was rewarded, partly by the power of deliberate survey of the countries through which the journey lay, and partly by the happiness of the evening hours, when from the top of the last hill he had surmounted, the traveller beheld the quiet village where he was to rest, scattered among the meadow beside its valley stream; or, from the long-hoped-for turn in the dusty perspective of the causeway, saw for the first time, the towers of some famed city, fain in the rays of sunset – hours of peaceful and thoughtful pleasure, for which the rush of the arrival in the railway stations is perhaps not always or to all men, an equivalent – in those days, I say, when there was something more to be anticipated and remembered in the first aspect of each successive halting place, than a new arrangement of glass roofing and iron girder.”

The year was 1851—clearly also the year of the run-on sentence—and people were already moaning about how others travelled. If, like me, you struggle with eliciting meaning from a 173 word sentence, Ruskin’s lament was aimed at trains—they were faster than the horse-drawn carriage he’d travelled in as a kid.

Narrowing the focus.

Writing in Slow Travel and Tourism, Janet Dickinson and Les Lumsdon write (far more succinctly than our mate Ruskin):

“The core of my argument is that travel not only takes time, but it also makes time.”

I like this line—a lot. Over the years, I must have written “Slow down and smell the coffee” hundreds of times. Spend more time doing anything and you’ll most likely learn something from it. Spending thirty minutes in Wogo village in Flores will obviously result in less learning than spending eight months there as Stroma Cole did in the late nineties. In Tourism, Culture and Development Hopes, Dreams and Realities in East Indonesia, Cole writes of the indiscretion of the belly button and the dreaded cropped top:

“A navel is a person’s centre, sacred and revered, and it is considered rude to put it on show. Pierced and adorned navels were met with horrified astonishment. As women said, ‘We just have to look away’, and another added, ‘How could they do that?’ ... Cropped tops, the most serious transgression of acceptable attire, were particularly popular in the summer of 1998 and provoked numerous debates about how to tackle the problem of ‘such rude tourists’ coming to the village. The fashion signalled a new type of tourist for many villagers, a particularly rude type.”

These sort of indiscretions point as much to poor guiding standards as anything else, but, the logic goes, if the cropped top wearer was travelling slower (rather than swapping Labuan Bajo for the alternative universe of Wogo via a few hours in a van) they’d have learned far earlier, and hopefully before causing offence, that cropped tops and belly buttons were a no no. Slow travel, in theory, should make for some lighter footsteps.

Just a few clicks to reach 100% Vietnam.

In today’s world, as the environmental impact of tourism has shifted towards the fore, the slow travel ethos shows promise. It eschews the whistle-stop style of travel popularised by travel companies, where itineraries are closer to that of a military expedition than a holiday, in favour of spending longer in each destination. The slow traveller travels by bus or train—or even bicycle or foot—and there are clear and positive environmental flow ons from this.

In my view though, there’s a bit more to it. Back to Dickinson and Lumsdon, on the underpinning of the tourism system, they write:

“Despite the decline in the popularity of the heavily packaged holiday and the rise of the internet as a main distribution intermediary, the structural elements of the supply chain have not changed radically. The process remains an essentially industrial one based on batch production of air travel, intense utilization of perishable accommodation stock at the destination and the creation of large-scale infrastructure ... to support the tourist flows stimulated through the marketing efforts of suppliers in a world of cascading substitutes.”

Putting it like that makes tourism sound positively Dickensian.

Airport, bus station, markets. Everything I need is on this map.

Slow travel is the antithesis of this. While I never thought I’d get to quote Dr Timothy Leary on Couchfish, and while I readily admit he probably didn’t have slow tourism in mind when he uttered his seminal “turn on, tune in, drop out,” the thinking behind it gels well. Leary was talking of becoming aware of alternate approaches, to act on this new awareness with the greater world in a harmonious fashion, and to build self reliance and seek detachment from “the system.” This is, in a way, slow travel.

There are though, three inter-related problems with it. Unless you’re Paul Salopek slowly walking around the planet, you’re going to be taking a long-haul flight or two, and it doesn’t get much more un-slow than that. Secondly, one of the reasons people take short holidays is because that is what they can afford, or they have work commitments that don’t allow them to, say, spend eight months in an Indonesian village. Thirdly, if an argument behind slow travel is to visit—and spend time in—the lesser visited, isn’t there a risk of simply broadening tourism’s footprint?

There’s no getting around the environmental impact of a long-haul flight. Some “slow travel thinkers” try by making it an in-destination process—ignoring the getting there bit when they pull out their slow travel abacus. Dickinson and Lumsdon differentiate between those who view the entire process and those who don’t as “hard slow travellers” and “soft slow travellers,” bringing to mind the whole backpacker or flashpacker debate. It is a practical approach I guess, but it feels disingenuous. The in-destination slow travel helps to mitigate one’s long haul flying excesses, but the elephant is there, squatting in the corner of the fan-cooled homestay room you cycled to.

Ahhh HCMC traffic—I have not missed thee.

While some may be time rich and money poor, often-case it is the opposite—the money is there, but there’s never enough time. After all, who has the money to spend six months a year travelling as a snail’s pace? For starters the wealthy do. This is a dilemma the slow food movement has battled with for years—the president of Slow Food USA, Josh Viertel, wrote as much in 2012:

“There are real, difficult questions at hand. What does it mean to promote paying the real cost of food while also promoting social justice and access? Is asking people to pay more for food elitist? Is exploring affordability an affront to farmers?”

To turn those questions to travel, is “true” slow travel an undertaking only the rich and shameless can afford? For this, I talked to one of my favourite slow travellers—and Travelfish member—Martín Aristía (who, as far as I know, is neither rich nor shameless). Aristía pushed back hard against my asking if slow travel was elitist.

“I strongly disagree with this idea. At least in my experience, it’s exactly the opposite: I normally spend far less traveling slowly than taking shorter holidays. Nowadays working online has become more popular than ever, so that also helps. You can travel slowly and visit two places in a two week holiday—this qualifies as slow travel to me—or you can spend two weeks at an all inclusive resort. By far, travelling slower will be far cheaper.”

His comment ties in closely with the rise of the global nomad phenomena, that travellers can today combine work and play to prolong a trip, perhaps indefinitely, in a way that 20 years ago wasn’t quite so easy—speaking from experience! I’m looking at Global Nomads in another piece in this series, so I’m not getting into it now, but it is worth keeping Aristía’s comment in mind. His argument, that slow travel, well, you can do it in a day, is supported by travel writer Lola Akinmade who says in this Youtube clip:

“I’m a big advocate for slow travel, but slow travel to me isn’t about duration but about your pace. So I can actually travel slowly, in one week, by slowing down my pace and choosing just one theme...”

Akinmade goes on to use an example of dance, and visiting a destination to learn about dance and the society and culture that revolves around it, saying this is preferable to:

“...running around trying to tick off everything .... so that can give you more meaningful slow travel experience even though it is a shorter duration.”

She covers similar ground in this episode of the Thoughtful Travel Podcast (if podcasting is more your thing than YouTube).

My God, there’s some trees the municipality mob have not cut down yet.

Yes, there’s still the flight to get there, but in the soft slow traveller realm, this view is a popular one. Slow down, do less, learn more—let travel make time. I like it, but let travel make time where?

As highlighted earlier by Cole, foreign travellers showing up at a village without being abreast of cultural norms can cause all sorts of misunderstandings. Đỗ Nguyên Phương is the co-founder of Slow Travel Huế, an agency in Huế that specialises in, well you guessed it, slow travel. In his view, a careful hand is required—both for the hosts and the guests—to make sure everyone is satisfied with how matters play out. He describes this as “Fulfilling in Connecting”:

“For us, we work with local people with a mutual agreement, sharing benefits. If travellers go on a full day tour, the farmer’s family who shares the farming experience will earn some income, as will the fishermen and boat driver, the family who offer lunch, and the ladies who make the sticky rice cake or conical hats—our host families are very proud to be involved. The guests are looking for authentic experiences and true connecting moments, and they are immersed into local life to share and appreciate these—even if there may be differences to their comfort zone. Our motto is “Fulfilling in Connecting” and for us, the quality customers are those willing to connect and share these fulfillments.”

Phương’s point here is an important one. It’s all well and good to say travellers should travel longer, deeper and slower, but there is little discussion about what the residents think about this. For decades, local communities have lacked a seat at the tourism table, their considerations and sensibilities an afterthought—if at all. Agencies like Phương’s, that are working to better vest these communities into the tourism process, are moving in the right direction.

Food joints start popping up willy nilly.

In a previous piece in this series, I wrote about pro-poor tourism in Luang Prabang, noting that one of the struggles was most visitors didn’t have the time to do overnight trips to outlying villages. This makes slow travellers—those who do have the time—a valuable asset for destinations like Huế and agencies like Phương’s. This is where I’d normally slip in a rant about how tourist visas need to be longer to enable longer, slower stays, but as I’m already way over my word count, you’ll just have to imagine it.

Which brings us to the money. The economics of slow travel, for the destination, can be persuasive. Independent travellers spend longer in destinations and travel farther, than regular short-stay tourists. Their spending is more likely to end up in the hands of small, family-owned businesses, rather than some travel conglomerate that is going to offshore half the funds into shareholders’ pockets. This matters.

Slow travellers though, can be a bit like three days, fish and all that. If they stay too long, the line between some variation on tourist and some variation on expat blurs. Rising property prices, creaking infrastructure, drugs, crime, racket and pollution—these are all standard issues when a destination gets “too popular.” It’s not only slow travellers who contribute to this—everyone does—but the longer one stays, the bigger ones’ contribution. What would Barcelona or Venice look like if every tourist who visited stayed a month?

HCMC is not a city—each city block is.

However many slow travellers there are, regardless of if they’re hard or soft, how they spend matters. This goes for all travellers, but for slow travellers in particular because, by their very nature, they stay longer and their spending habits are repeated over and over day in day out. The positive one brings by staying in one place a long time dissipates fast if the spend is primarily at foreign-owned clubs, on imported food and booze, or to a foreign landlord.

To look at travel through a carbon lens (more on this in another story in the series), transportation comprises the majority of the overall emissions of a trip. So, if this matters to you (and it should), then even though you’re still flying long haul, reducing your transport requirements while in-country is an obvious step in reducing the carnage—but probably equally important is how you spend your money while there.

To my mind, slow travel is a pretty good bandage but it only covers half the wound. I’ll be looking at the other half in a few days time. In the meantime, spend a day exploring that single city block in Ho Chi Minh City—just don’t wear a cropped top.

Other episodes in the Rethinking Tourism series:

National Chocolate Milk Day (World Tourism Day)

Nice Tourism (Sustainable Tourism)

The Benevolent Lie (Responsible Tourism)

The Year Is 2006. The Town Is Luang Prabang (Pro-poor Tourism)

Zoom in to the Red Plastic Chairs (Slow Travel)

The Petro-bourgeoisie (Flying, carbon etcetera)

Reality Check (Tour companies)

Follow the Money (Money matters)

Foundations Matter (Community Based Tourism)

Couchfish is 100 per cent independent and reader-supported. If you’re not already a subscriber, and you’d like to show your support, become a paying subscriber today for just US$7 per month—you can find out more about Couchfish here—or simply share this story with a friend.

Don’t forget, you can find the free podcasts on Apple, Pocket Casts and Spotify as well as right here on Couchfish.

Share this post