In September Google announced they wanted to build a sustainable future for travel. Don’t we all? Well, many of us anyway.

You can read Google’s announcement here. To boil it down, what they’re doing is adding an “eco-verified” tag to “accredited” properties listed on Google. Readers can then click on the link to get the wrap on which boxes the property is ticking. This was right around when they joined Travalyst—a non-profit garbage fire of corporate blather and buzzwords about mainstreaming sustainable travel. It is run by some royal dude. As you may have gathered, I’m not much of a fan.

One is more sustainable than the other. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

The other big bit of news on this front is a Booking.com report (PDF) which came out earlier this year—that its title photo is of Kelingkling Beach on Nusa Penida perhaps indicates its awareness of sustainability (pre-Covid19 Kelingking was a mess of over-tourism). The relevant headline figure was:

73% of respondents “would be more likely to choose an accommodation if it has implemented sustainability practices.”

I wonder how valid a reflection this is on the real world. If it was accurate you’d think the hotel scene would be far more sustainable than it currently is.

I talked to three small hotel owners while writing this, none said queries around sustainability were common. One summed it up as:

“People already know we are are as eco-friendly and sustainable as we realistically can be. They don’t need to ask, and we certainly don’t need this sort of labelling. Who is really driving this? Why?”

Said another:

“No, guests don’t ask before they book, but they appreciate the efforts we’ve made once they get here. The awareness raising of this is good, buy paying some outsider a fortune to tick a box to verify we are doing what we already do, is bullshit.”

Anyway, back to Google. Ticking is exactly what is happening, as Google being Google, they’re not verifying anything. That instead, is left to a glad bag of “certain independent organisations”. Google currently lists 29 which meet their standards of eco-certification. Google doesn’t say what their own mysterious standards are of course. Says Google of the list:

“Each has comprehensive and rigorous sustainability criteria that aims to reduce a hotel’s carbon footprint.”

I’m being a bit unfair on the mysterious front. Google does throw us a bone—five categories it believes are important. They are:

Energy from carbon-free sources

Locally sourced food and beverages (Google considers within 100 km to be local)

Organic cage-free eggs

Eco-friendly toiletries

Responsibly sourced seafood

Sounds like a start I guess. It isn’t clear if you need to meet all these to be certified. I doubt it. Take seafood, Google defers to Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch for guidance. Mahi-Mahi is listed on their “avoid” list for Indonesia. Anyone who has eaten seafood in Bali will know this is one of the most frequent fish you’ll see on a menu. So if you sell Mahi-Mahi but friendly eggs, can you qualify? It isn’t clear.

Seafood lunch in Amed. Line-caught by a local fisherman. Wrong fish? No eco-certification for you. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

This is only a sample of Google’s criteria though—the accreditation agencies are a whole other beast. I started with the Asian Ecotourism Standard for Accommodation, as they appear to be Southeast Asia focused. They have a helpful PDF guide on their sustainability guidelines.

Like many of the organisations, you’ll need to be able to count real high if you want to count words like “try”. There’s little in the way of hard benchmarks. Take cooking oil for example. The PDF asks “Do you effectively reuse or recycle cooking oil?” The performance indicator: “Where available, use the used cooking oil as fuel and/or soap.” What it should say, is something like “To qualify for this certification, you must use X% of your used cooking oil as a fuel or soap.”

EarthCheck has featured prominently in media coverage of Google’s announcement. Let’s take a look. For starters, this Australian organisation is a bit of an exclusive club. Membership goes for A$400 per month and the audit fee is a mere A$2,420 for the first day and $1,650 for each extra day required. Best aim for an action-packed first day I reckon.

Before anything else, how many small, family-owned businesses in Southeast Asia are in a position to cough up fees like this?

EarthCheck has a handy map of businesses that are in their system. The closest two to me are the W Bali Seminyak and Alila Seminyak. Both break Bali’s build back rules (to be fair as does almost every beachfront property on the island). Maybe that is why they only got a Silver Certificate. But what does a Silver Certificate mean? Despite my best efforts, I couldn’t find a clear explanation on their website. There is this checklist but it isn’t clear how this ties to silver or platinum or copper or whatever.

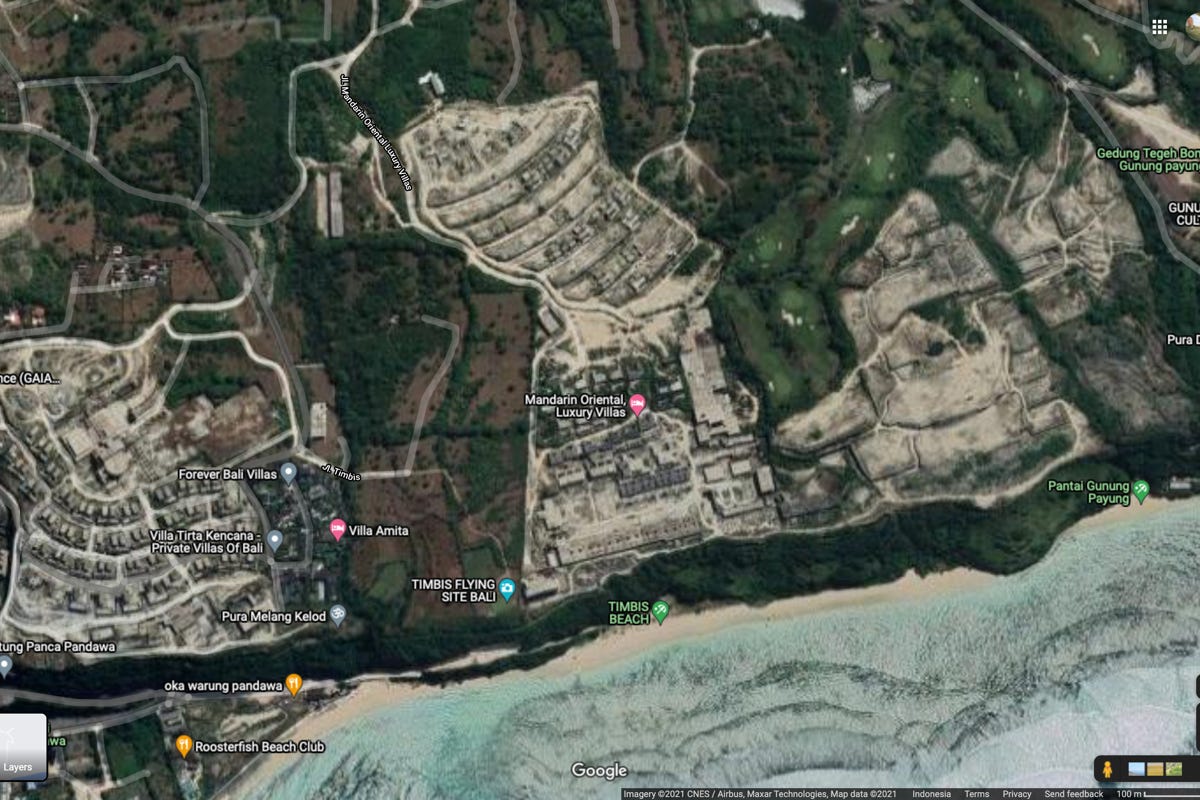

Platinum. By Bukit standards, Alila blends in I guess. Screenshot: Stuart McDonald.

I did note that Alila Villas down in Uluwatu scores even better—platinum no less. Above is a screenshot of their property in South Bali via Google Maps. How does a property with at least 56 private pool villas, built in an area with near no natural water, get platinum certification? Maybe they compost. According to their sustainability statement, they say:

“We are proud that Alila Villas Uluwatu has embraced environmentally sustainable design (ESD) principles and is the first resort in Indonesia to receive the highest level of certification from EarthCheck as a Best Practice Building Planning and Design (BPDS) development. We utilise many ESD measures, including use of local materials, water conservation with soaks and rain gardens and a wastewater management system, using local plants from the special Bali savannah ecosystem, the deliberate use of sustainable/recycled materials, protection of the natural environment, and measured work practices throughout construction.”

The fact remains though, there are at least 56 private pool villas where before there were none. Why isn’t this a part of the eco calculus?

I don’t mean to pick on Alila here—at least they do compost—and plenty more if you care to look at their statement here.

Down the road from Alila. This is why the original footprint matters. Screenshot: Stuart McDonald.

Alila’s good work, brings to mind a side note—wouldn’t a simpler approach have been for Google to simply link to hotels’ eco and or sustainability pages? Oh wait, that would involve leaving Google. Google may want to make travel sustainable, but please do your sustainability research on Google.

The last organisation I want to look at is that of Hostelling International. Hostels aren’t a thing in Southeast Asia in the way they are in the West, but this is the best I could find aimed at budget properties. As with the Asian Ecotourism Standard for Accommodation, there’s talk and guidelines, but no hard targets. Take this, on water:

“Water consumption is measured, sources are indicated, and measures are adopted to minimize overall consumption.”

In practice, what does that actually mean?

Don’t get me wrong. Just the other day I was writing about how travel publishing needs to ask harder questions of hotels. All these guidelines are at least pushing some operators in the right direction. They are also raising awareness—they’ve got me writing about it after all!

Ticking sustainability left, right and centre, but not approved by any Google-chosen mob. No green tick for you. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

That said, marking these places as “eco-certified” is misleading, to say the least. Yes, it is good to compost—it is how we got our papaya tree. Or to use the right lightbulbs—who doesn’t want a mix of yellow and white bulbs illuminating their lounge room? A small price to pay for a better planet right?

The problem is, as far as I can see, the initial footprint of the property is not taken into consideration. That a resort can go build whatever, wherever, then receive environmental accolades, strikes me as absurd.

All of these schemes need to take the initial imprint of the place into account. What was there before? Was natural forest removed? Is there fresh water available? How much extra electricity was needed to turn the lights on? How much stuff needed to be imported to build the place? How much labour was drawn from local communities? Are employment contracts fair? How much of the hotel’s spend is within the local community? Was public beach access removed when the property opened? I could go on, but you get the idea.

Joni Homestay, 10km from Nihi, in Sumba. Certified friendliness—that’s what I want. Photo: Sally Arnold.

Some properties will do better at answering the above than others. I’m sure some won’t want to answer any of the above … at all.

But if you’re going to certify a business on an environmental or sustainability calculus, do it properly. And don’t do it in a manner that immediately discounts small properties that were already on the right track before Google suddenly decided the environment of travel mattered.

Couchfish is 100 per cent independent and reader-supported. If you’re not already a subscriber, and you’d like to show your support, become a paying subscriber today for just US$7 per month—you can find out more about Couchfish here—or simply share this story with a friend.

Don’t forget, you can find the free podcasts on Apple, Pocket Casts and Spotify as well as right here on Couchfish.

Share this post