A quick note, save a series conclusion running tomorrow, I’ll be back to regular programming on Monday. Yay!

On one of my very early trips to Thailand, I lost a few weeks at Hin Wong Bungalows on Ko Tao. Set on the back side of the island, you’d approach on a longtail from the port. It was quiet. Very quiet.

My hut was a wooden bungalow on the rise, with a bathroom down the slope a bit. The only furniture was a mattress and a hammock on the deck. There was no beach to speak of, rather large boulders you could dive off into the crystal water. It was, for years, my favourite place.

The 1993 Hin Wong view—no complaints. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

This was pre-The Beach, yet echoing the book’s (and later film’s) plot, a previous guest had drawn a map on the interior wall. It was a rough charcoal outline of Thailand, and the traveller had annotated it with their wanderings. Chiang Mai had some hills and an elephant, Bangkok some “sexy ladies,” and Railay had its cliffs and a sunset. Hin Wong on Ko Tao was also marked, with the emphasis on a swim-through out in the bay. Around the map, arrows pointed in, with the names of places to stay. Linda Guesthouse in Chiang Mai for some reason still sticks in my mind.

It was one traveller’s guidebook, marked up to share.

Democratise My Travels

Back then, guidebooks did near all the guiding. There were no TripAdvisor or Agoda people, and no Pinterest or TikTok travellers. Instagram? If someone had said that to me, I’d have assumed it was a reference to buying drugs. Google? It didn’t exist. At least in the circles I mingled, you were either a Rough Guides or Lonely Planet person.

Today, a traveller might be using all the above sources—and dozens upon dozens more—for their travel planning needs. Magazines and Pinterest for inspiration, OTAs for hotels, food websites for stuffing face, Google Maps for everything. Instagram for bragging.

Somewhere on Lombok, where, just an hour away, the beach is packed. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

With this democratisation of information, you’d expect trips to have become more diverse. In practice, the opposite has happened. I’d bet my flip flops that if you visited a third-tier destination in 2019, you’d have found fewer tourists there than you would have in 1999.

A part of the answer to the question of why, is that the internet changed travel writing’s incentives. Guidebooks sold you a book, and the book—at least in theory—contained information that helped you have a better trip. With the internet, the reader became the product as websites sold your interests to advertisers and gave you the travel intelligence in return. They also sold you a whole load of swag—as travel writing went retail.

Over in the dead tree side of the industry, outside of guidebooks, travel writing’s role as the PR wing of the travel industry ran sordid and deep, and had done forever. In Elizabeth Becker’s Overbooked, she notes that by the 1960s “travel” accounted for 25% of newspaper ad revenue, yet there often wasn’t a firewall between advertisers and writers. Not content with buying ads, free trips became the norm. Comparing travel to political (where—again in theory—political parties don’t pay journalists’ expenses), Becker writes:

“That would be declared corrupt and the antithesis of ethical journalism. Yet it is the engrained way of writing about travel in the United States, much of Europe and Asia. ... The editors told themselves it was the only way they could afford to cover the travel world. And the public relations professionals were thrilled, knowing that a handsome write-up or recommendation in a magazine was far more credible than an advertisement or brochure.”

Becker’s take though, was hardly news. Writes travel writer Elizabeth Austin—in 1999—of a press trip to Bali:

“I was a travel whore. This is my story.”

Fill My Wallet

When online income streams appeared, new media, Travelfish included, adopted them with enthusiasm. “Add this code to your site and the money will roll in,” and it did.

Did these monetisation schemes skew coverage? Yes. On Travelfish? Yes. How? To garner more search traffic, we fed the beast with hundreds of pieces, all to run ads against—oh and inform! When the bottom fell out of ads, we moved to hotel reviews, and went nuts there instead.

Pai, Thailand. Google said to list everything. Photo: Mark Ord.

Over the years we’ve reviewed 8,685 properties, and to a point the effort paid off. Yes we helped thousands of readers find great places to stay—but we also earned plenty through affiliate commissions. I still remember the day we received a commission of over US$1,000 for a single hotel booking. It is to be fair though, easy to remember as this only ever happened once! That booking, through an OTA for a luxury hotel on Thailand’s Ko Samui, is instructive.

The real money for publishers, be they a travel blog, website, magazine or newspaper, is in lux travel. The highest impact sector of the tourism industry? The luxury end of the stick.

In our case, we had a separation many if not most others didn’t. We never took free stays or media rates. We always paid our own way. We reviewed in an anonymous and independent fashion. We had a gaggle of middle-men running interference between us and the hotels. We always listed the property’s direct contact details. Despite all these steps, to me it has always felt a bit icky—but hey, it paid the bills.

Hell No

I’ve debated comps with many professional writers, friends who argue the comp doesn’t play a part in what they write. I believe them when they say they believe it. A talented writer should be able to write in an independent fashion. When I ask if they’d have written about the place—or even visited it—if they’d have had to pay themselves, the answer is near uniform:

“Hell no.”

Madelaine McWha et al., in a paper looking at sustainable travel writing notes:

“Traditionally, many travel writers, as well as travel writing in general, have been associated with commercial imperatives to sell travel destinations, and hence perhaps the promotion of travel more aligned with unsustainable types of mass tourism.”

Go pick up a copy of CondeWhatever and take a leaf through—look at the ads and the copy. How many affordable homestays do you see? What does an affordable homestay have to do with anything? How does this play into responsible travel and/or sustainable tourism?

At Happy Homestay near Cao Lãnh in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. Absolutely responsible “per se.” Photo: Stuart McDonald.

EXO Travel Group has been busy for a few years working to measure the carbon emissions of their trips. I asked Alexandra Michat, their Chief Purpose Officer, about how they deal with hotels. I was curious about budget joints, places that lack the funds for certification pyramid schemes. Her answer by accident dovetails with travel writing and sustainability:

“... we’ve realized that most of the time “Responsible hotels” were internationally owned /managed and they were getting higher scores because they already had policies in place and strong financial capacities etc rather than independently owned properties and/or homestays, therefore we usually consider homestays as responsible ‘per se.’”

These places, which EXO usually sees as “responsible ‘per se,’” tend not to feature on journo comp lists. Yet those on such lists—and that do get written about—are often far from enviable on the sustainability front. They do though have bamboo straws.

In Tourism Leakage of the Accommodation Sector in Bali, Suryawardani et al., looked at hotel leakages. They found that typical four- and five-star hotels in Bali had a leakage rate of 51%. At the other end of the stick, budget places, the leakage rate was a mere nine per cent. From a sustainable tourism point of view, this is bad, yet it is the four- and five-star sectors that features most often in contemporary mainstream travel writing.

Gimme the bad news

Academic Ben Iaquinto has written quite a bit on backpackers and both their good and bad habits. Touching on Lonely Planet’s mainstream shift, he quotes an (unfortunately un-referenced) comment:

“Once, a number of young women had written to LP to report being raped by a certain proprietor in Southeast Asia and the local tourist board took legal action against LP for warning young women to avoid that establishment. This sort of thing eventually led to the directive ‘If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all’. I believe that this does a disservice to travellers.”

Keeping to this theme, a highlight of 2020’s news cycle was the traveller who got jailed over a hotel review. Unhappy with a hotel on Ko Chang in Thailand, they took to TripAdvisor to vent and got jail time for their efforts. As a travel writer focused on Southeast Asia, I’d be lying to suggest certain legal regulations don’t have a chilling effect on what I write.

Today, the impact of tourism development exacts a greater toll than ever. Yet, taking a name and shame approach to writing on this, is, well, often not all that sustainable for the writer. The Deportation Express is always on call. The alternative then, is to ignore the bad and focus on the good, and hope readers can read between the lines. It is far from an ideal situation.

Whose gaze

Take a look at the list of interviewees in the McWha et al. paper mentioned above, and tell me what is missing. In a related paper, the author notes the writers were “largely from Australia, New Zealand, UK and USA.” Travel writing in the English language has for decades been dominated by white men of means (like me, except for the “of means” bit). Today there’s plenty more women writing, but the trade remains predominantly white.

She’ll know more than I ever will. At Xẻo Quýt in the Mekong Delta. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

With this comes a glad bag of -isms and other challenges for the writer. Exoticism, colonialism, genderism, objectification, orientalism, and so on. These have all featured in academic literature on travel writing for decades, but out here in the real world, change—or even awareness—is low. Though you can do a course on it for $215 a head. This piece, by Chloe-Rose Crabtree, raises plenty of solid reasons for change.

Travel writers often see themselves as mediators, explaining the unfamiliar to readers. Done well, this can have a positive impact on both the readers’ journey and the hosts’ experience. Yet, why are travel publishers relying for a large part on white writers? Where is the diversity of voices? More often than not tour companies will highlight their use of local guides. Sure it is the law in most countries, but the companies clearly feel it is a selling point as well. Why don’t travel publishers feel the same way?

Since going online in 2004, Travelfish has had 95 contributors—including me—of whom 46 were women. Three contributors were from Southeast Asia—two Singaporeans and one Thai. How bad is that? Pretty bad. I could make excuses for the sad state of affairs, but I’m not going to even try—it is inexcusable. This isn’t to say our contributors were not excellent, they were. That said, as soon as we’re employing again (who knows when that will be), this will change. Better late than never and all that.

Walk the talk

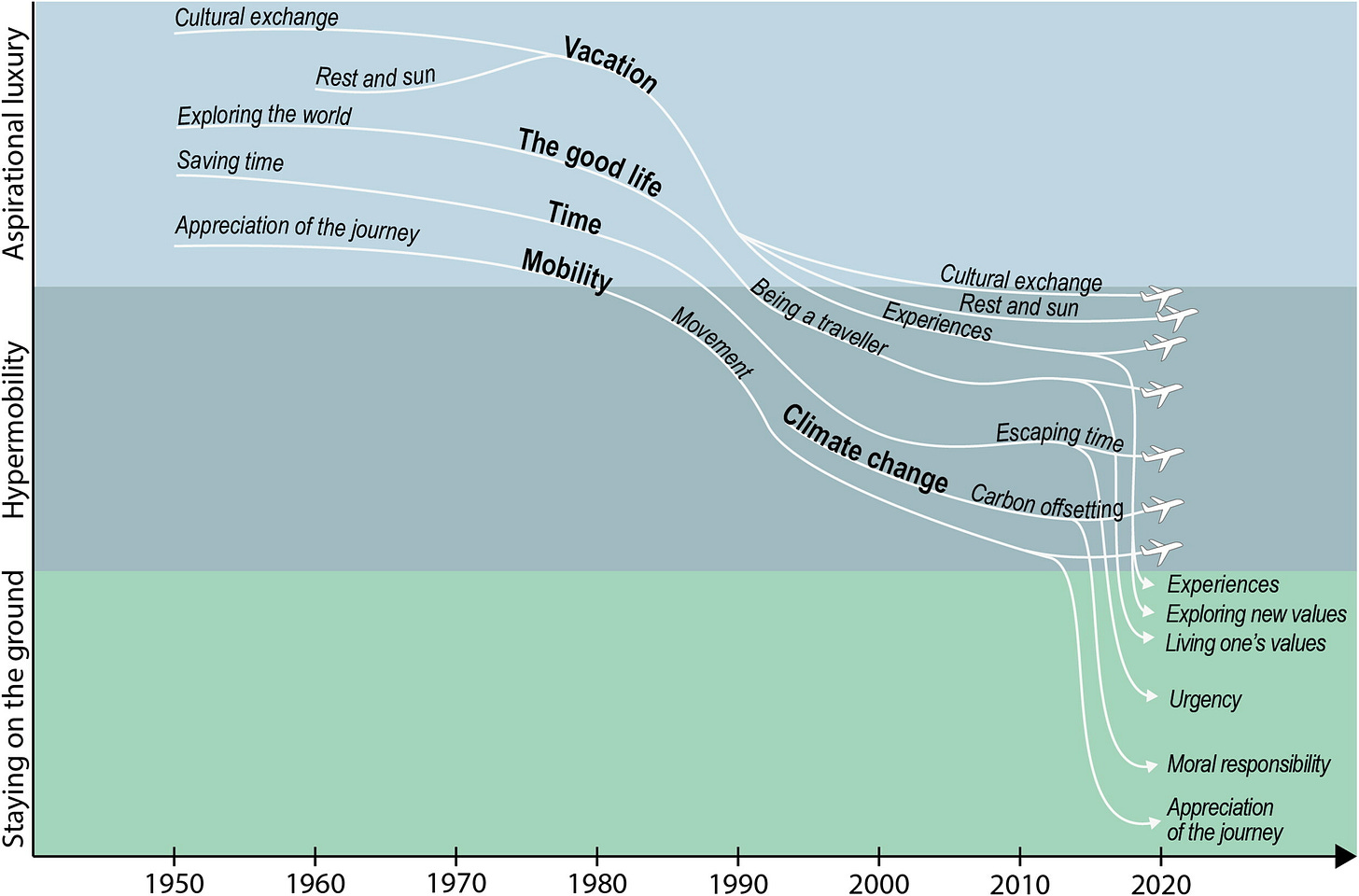

Despite these flaws, good travel writing, be it service- or long-form- can be an agent for change. In 2021, Sara Ullström et al. published research that looked at the travel media’s role in changing conversations around holiday air travel in Sweden. They wrote:

“As a response to the urgency of taking climate action, and the importance of living one’s values and taking moral responsibility for high-carbon practices, flying is problematized while alternative ways of travel are valorized. In this way, Staying on the ground shapes people into questioning, and in some cases ultimately changing, their travel behavior.”

As I’ve touched on over and over in this series, many (some more than others) are working to ferment change. Some are drops in the ocean, other ripples, others still small waves. In almost every case though, there is as much a need for change from within as out there.

Source: From aspirational luxury to hypermobility to staying on the ground: changing discourses of holiday air travel in Sweden.

Reports like the one out Sweden give me heart. It shows me that change can be wrought outside despite disfigured internals. This also goes to show how much change could happen, if the companies—Travelfish included—changed first.

Old school still works

A couple of years later, back on Ko Tao, most of the charcoal rendering of Thailand had faded away. Others though, had added to it. Cambodia was there and a poor take on Vietnam. Some tips were scratched in with cheap biro or coloured markers. Off to the side, another traveller had added a beautiful painting of Malaysia’s Perhentians. There were beaming turtles between the two islands and a gleaming heart by Adam and Eve Beach. The tips on the sides of the art? Dozens more had appeared.

It was pretty cool.

Other episodes in the Rethinking Tourism series:

National Chocolate Milk Day (World Tourism Day)

Nice Tourism (Sustainable Tourism)

The Benevolent Lie (Responsible Tourism)

The Year Is 2006. The Town Is Luang Prabang (Pro-poor Tourism)

Zoom in to the Red Plastic Chairs (Slow Travel)

The Petro-bourgeoisie (Flying, carbon etcetera)

Reality Check (Tour companies)

Follow the Money (Money matters)

Foundations Matter (Community Based Tourism)

Couchfish is 100 per cent independent and reader-supported. If you’re not already a subscriber, and you’d like to show your support, become a paying subscriber today for just US$7 per month—you can find out more about Couchfish here—or simply share this story with a friend.

Don’t forget, you can find the free podcasts on Apple, Pocket Casts and Spotify as well as right here on Couchfish.

Share this post