Every now and then in my travels I stumble upon a spot that is so perfect—for me—that I think I never want to leave. Then I meet the people behind it, people who manage to make the perfect even moreso, and I know I never want to leave.

Kepa Island, a smudge on the map, off the western tip of Alor, part of Indonesia’s Lesser Sunda Islands, is such a place.

Exploring Alor. Should have put in a longer leave form. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

I first came across it on a research trip in the region. I’d been dossing in Kalabahi, the capital of Alor, exploring the island, but I wanted to find something on the beach. I’d read about Kepa and that it was home to a European–run dive resort, but I’d stopped diving, so the appeal was limited. Plus I wanted something more beach bummy—I put it to the side.

Alor is vaguely chicken–shaped, and I’d ridden all around the “head” looking for places. Some beaches were fantastic, but either lacked accommodation, or had only grimy losmen. Kalabahi, is ok, but what I was looking for—beach bungalows—seemed not to exist—at least not in an accessible spot.

A Kalabahi sunset. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

I bit the bullet and sent a WhatsApp message to the number I had for the dive resort. Did they have a room for non–divers? They did. The next day I got an ojek over to the boat landing.

Somewhere to put your bag

Kepa is a rock. It has no natural water, and much of it is, well, a rock. On the north coast though, sits a small French run resort, L’Petite Kepa. In business since the mid 90s (depending on how you define “in business”), it offers rustic digs in a spectacular setting.

A traditional hut with a view. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

I ask co–founder Anne why they picked Kepa. She tells me they were travelling in Indonesia in the mid nineties, and her partner, Cedric, was a keen diver. Says Anne:

“We were young ... I’d finished my studies ... Cedric started travelling in Asia [in 1994] and finished his trip in Indonesia ... he likes very much Indonesia. I come back to France, he comes back to France, I start to work ... and Cedric started to travel more. Travelling six months, working six months, and of course I was coming back to Indonesia more.

And so then, we started like a lot of people I guess, starting to speak Indonesian because it makes it easy to meet the people and we like it very much. He was travelling quite off the beaten track, and he knew this area, lets say the east, had some good sea. Then he came here, and there was nothing and he liked it and that’s it! ... He wanted to stop to travel but to put his bag somewhere.”

I interview Anne for 45 minutes, but “Somewhere to put your bag”, more than anything else, hits home. Sometimes you find a place and you just want to put your bag down—for a long time.

Lost backpackers

Remote is relative, and while low cost flights have made Alor more accessible, in the early days it was anything but. Says Anne:

“For two years I think, there were no flights anymore between Bali and Kupang, so it was a Pelni ship from Bali to Kupang. That took three days. Then from Kupang take the ferry to Kalabahi, 18 hours. It was quite a long trip but it was nice, because it was really rural Indonesia. This was more than 15 years ago, which means no motorbikes at all, very few boats, a lot of small sailing boats. It was quite remote. So our idea was more to have a place to come back to and I don’t know, to spend a few short months living a simple way.”

Our family house. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

When I ask who their guests were back then, who had the time for journeys like this, Anne laughs:

“Lost backpackers.”

A simple life

There’s no denying, almost twenty years later, that life at L’Petite Kepa is simple. The accommodation is simple. There’s no air–con and the loos are bucket flush. If you want hot water, staff will give you a large black rubber bladder to fill up with cold water in the morning. You lay it on the lawn throughout the day. Come the evening, you pour it into your mandi, and you have a warm shower. Magic.

Maroon me at the back beach please. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

When I return the next year with the family, we rent a larger wooden house. It costs a little over 1,000,000 rupiah per night for the four of us, full board. It is a two bedroom affair, well one master and the kids’ bed by the living area. The kit out is simple. Thin mattresses, a bottom sheet, a couple of pillows and a mosquito net. But it is all we need. We have a large deck, perched by the cliff. At high tide the kids lay around and spot reef sharks in the shallows.

Me, less time for shark–spotting more for working. Our living area has a writing desk flush against a large un–glassed window. Every morning I set up there, laptop humming and look out the window.

Low tide views across to Ternate. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

There’s the beach, then the house reef, then, beyond it, Ternate. Not the better known one, but it shares the same name. It towers before me. Jurassic.

It is a beautiful spot, but beauty can be deadly. The currents are dangerous and people swimming off Kepa have vanished without a trace. Get caught in the current and it is next stop Timor—or Australia. On check–in there is a detailed talk on where is safe and where isn’t. The back beach is good on this tide, but do not swim on that one. The briefing is friendly, but serious.

The ocean demands your respect.

Swim o’clock. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

For us with the kids, it is no big deal. The powder white sand back beach is so gorgeous that when the tide is wrong we build sand castles, read or snooze. When the tide is right, we swim with baby reef sharks and snorkel out to the drop off—the big blue racing by.

A family feeling

Other guests are an eclectic mix. Yes, some are diving bores, but others have fascinating and varied histories. My favourite is a Roman couple. He’s a gifted photographer, but in a previous life was a journalist. His claim to fame? Being one of the first Western journalists to interview Aung San Suu Kyi after her release from house arrest. It was only post interview he realised his recorder was on pause. Another is an Indonesia–based French photographer. To this day, she fills my Facebook feed with drone photos of amazing beaches in this beautiful country. She never says where any of them are and it drives me nuts!

My old man chair. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Often resorts in remote parts of Indonesia will draw staff from Bali, due to perceived skill shortages. This is not the case at L’Petite Kepa—all Anne and Cedric’s staff are from the local community. They’re far from what you’d encounter at a front desk in some fancy pants Balinese resort. Instead they’re welcoming and forever assisting—reinforcing the family feeling for guests.

This also strengthens the bonds between the resort and the community. During another chat Anne mentions how many people they’re responsible for and I’m staggered. I say I’m surprised the number is so high. Anne explains that over time, as the resort grew so did their shadow. The way she talks about them, is as you would one large extended family—they’ve become part of Anne and Cedric’s life and them theirs.

Magic is a kind of diplomacy

In the early days, Anne worked with an NGO in the region, and later with a seaweed project on neighbouring Pantar. We get onto this topic via a circuitous route talking about black magic. While you can encounter this across Indonesia, like Nusa Penida off Bali, Alor is famous for its magic.

No need for Photoshop. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Across the water lies Pantar. Anne tells me a convoluted tale about a disagreement between communities over seaweed farming. Matters came to a head—well, came to machetes to be exact. Despite attempts by one to behead another, the machete “just couldn’t hit ... there was not a drop of blood”. She suggests feigned attacks for the lack of any real loose heads, but the story reverberates through the community as something else. “We tried to kill you, but your magic was too strong.”

“Magic is a kind of diplomacy”, Anne says.

Around off the back beach there is Kepa’s main “magic spot”. The place you go to make offerings for a safe journey at sea, to sacrifice chickens, or, boil rice in sea water to cast some bad juju towards another. It is a difficult time at the moment as what Anne calls “the tribe tree” has died. Locals are concerned about what it means. Anne gives me detailed instructions on how to find the spot, and I go looking for it. I get lost and instead find some beautiful coral off another beach. The underwater world here is magnificent.

The big blue

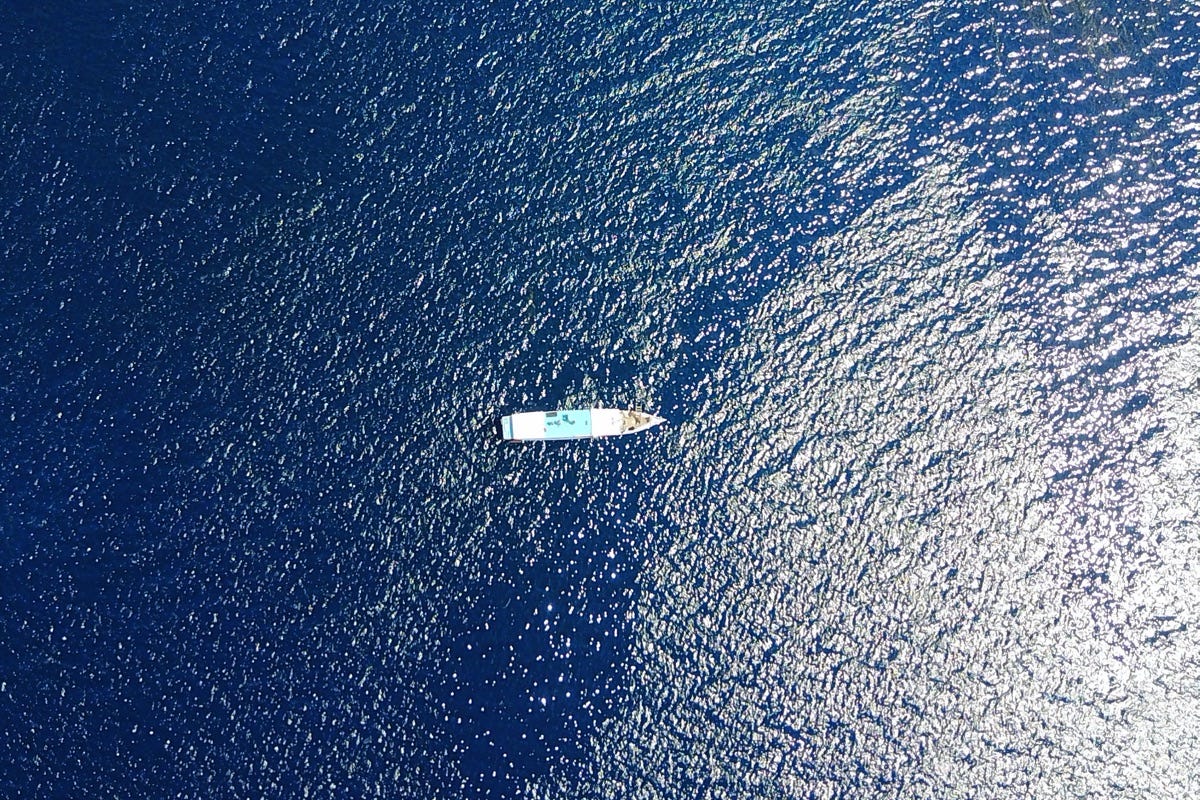

One day the kids and I join the dive boat. We’re not diving, but we’ll be able to snorkel. One of the other guests has a drone and as we lay over a reef off the north coast of Pantar, she sends it sky high. Later, back at the resort, she shows me a still. It is this magnificent feat of isolation. Us and the big blue. I love it.

My kind of isolation. Photo: Emma Davidson.

The house reef can only be safely snorkelled at certain times. I swim out to the drop off with the kids. The current grabs us and pulls us all the way around a third of the island, depositing us half an hour later, at the boat landing. We walk back around and do it again. And again. And again. The reef is in good condition and there is plenty of sea life. Reef sharks dart by in the shadows.

On the cliff, near the restaurant, there is a solitary old man chair. I need to clamour up sharp stones to get to it, but once on it, I’m suspended above the cliff. Depending on the tide, below me is gleaming white sand or turquoise water. In the distance, as always, Ternate.

Chill out here; Photo: Stuart McDonald.

On another vantage point, a wood and bamboo shelter waits for lovers. The kids swing behind it in their hammocks. The sunsets from here are magnificent.

It feels like home

L’Petite Kepa is full board, meaning three meals a day are included in the price. All are communal, and the food predominantly Indonesian. Often out East you find your self eating fish and rice or rice and fish, day in, day out. Here, despite the location, the fare is more varied—and excellent. The communal setting makes for an easy way to get to know other guests—our temporary family. Anne, Cedric and sometimes their two daughters, often eat with us.

The Romans about to go for a sunset snorkel. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Arriving as a non–diver at a dive resort, sometimes leaves me feeling like an interloper. Not at all here. It feels like home—and I can’t wait to be able to get there again.

Note: Due to Covid19 L’Petite Kepa is currently closed. Please see their website or Facebook page for more information.

Share this post