A month or so ago, my friend James sent me a link for a travel guide to Cambodia. James has a particular talent for sending me stuff that ruins my day, and this one, well, it was a doozy.

It was one of those typical “how to” travel blog pieces, with blow-by-blow instructions on how to do something. In this particular case, it explained how one can travel from Siem Reap to Phnom Penh by train. Over three thousand words long, it had everything—it even detailed the restaurant and drinks car.

There was though, one problem. There is no train—and never has been—from Siem Reap to Phnom Penh.

“You want a what to where? I’m telling you there’s no train man.” Photo: Mark Ord.

I wondered, why would anyone write this? I could see no useful reason to. The more I read it though, the more I thought, was this the pointy end of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) stick? I emailed the site, and asked after the reasoning behind the piece, but never heard back. I ran some of the text through GPTZero, a tool (yes, an AI tool) designed to detect AI written text and it said:

“Your text is likely to be written entirely by AI.”

AI has been flavour of the month for a while now. It was a few years ago I first saw it in action, and it wasn’t great. Even then though, with improvement inevitable, its potential was clear. I remember writing at the time something about it being the death knell for low-end copywriters. Late last year, ChatGPT opened up its playground for free. It is the brainchild of OpenAI, a startup which includes Elon Musk and Peter Thiel—neither renowned for putting humanity first—among its funders. The opening (now partly rescinded), brought the tool to the masses, and was no doubt the first step towards the funders’ inevitable mega-payoff.

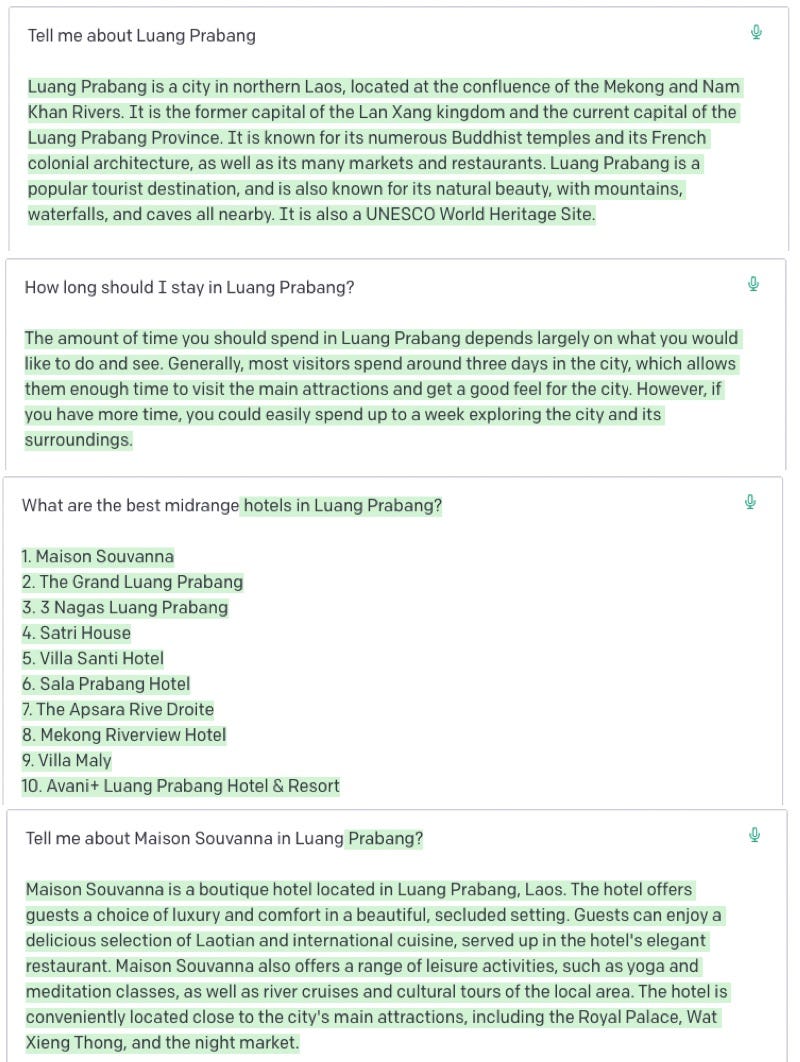

Lets get ChapGPT to write a travel guide for Luang Prabang.

Social media filled with screenshots of the tool’s efforts to “answer” questions. Many, (not only from ChatGPT) veered between bad and iffy to awful and offensive, yet others were eerily good—including poetry, though not poems about athletes foot. To get decent answers, the right questions, in the right way, with the right degree of post-output massaging, were needed. In no short time stories by the dozen ran—sometimes of dubious quality—pointing out AI often displayed a racist and/or sexist tilt with a tendency to surface hate speech (which OpenAI pays Kenyans $2 per hour to address) and disinformation. This is all true, but you could argue if it aims to mimic humanity, this is sadly it doing its job.

Let’s return to the train example for a sec.

With the right collection of keywords, a bit of programming skill, and a dose of patience, AI could write a travel guide. I’ve tried to illustrate this with the (unedited) screenshots in this story. As you can see, AI can already manage a good bit of the process. The finished product isn’t great, it is often boilerplate bare bones, with a few factual errors, but as a collection of lists, it could be far worse. With this text generated, all I need do is dump it into Wordpress and I’m done. I’ll do another city over lunch. In that time, AI may well have improved yet again.

Note the different results when I complicate the question about Saffron Hostel.

How will it improve? To answer this, you need to look at how AI works. Boiled down, it crawls a bazillion websites then regurgitates the information it distills. This means it is only as good as the information it has devoured. If it hasn’t ever crawled information about the mating of the Mongolian Butterfly, it can’t tell you anything about it. As far as I know, there is no such thing as this specifically named butterfly.

Now for the important bit. This crawling of information sources took place without any consent from the creators. Nobody asked Lonely Planet, Getty, or other creators for permission and it should come as no surprise that courthouse queues are growing. It boils down to consent. These tools should be opt-in but instead, if at all, they’re opt-out.

ChapGPT’s take on eating in Luang Prabang.

Says Michael Running Wolf, an AI ethicist, and founder of Indigenous in AI, in this fascinating episode of The Sunday Show [any transcribing inaccuracies mine, it is a bit fuzzy in places]:

“The core conceit problem here isn’t the fact that the AI exists, it’s because they’re stealing data to create these AIs. If we had the ability to enforce our intellectual property rights either through some sorta legal entity who owned the data or even as artisans being able to stop it, this wouldn’t be a problem actually. The whole reason why you can have StableDiffusion, DALL-E ... there’s many other AIs out there, is because they scrape the internet. These AIs have seen Lakota artwork, these AIs have seen Lakota artisan work and pictures, and that’s why they can do it. If they don’t see it, they can’t do it.”

Sarah Andersen, an artist involved in a legal case against a number of AI engines, echoes this in an interview on Hard Fork:

“And I think for me, the big one is consent. People have talked about that maybe in the future artists will be able to opt out. For me, that’s not good enough. I really think if this is your life’s work, as an artist, you should be able to opt in. It should be up to you about whether or not you are part of these generators.”

If the sources of AI’s “intelligence” had needed to opt-in, AI would have had a far smaller information set to work with—and the results would be far less amazing—and no doubt attract less hyperbole … and less money.

Note the first attempt at Kwang Si was wrong, I had to add the Luang Prabang prompt to get the right waterfall, though you can’t see the falls from the Nam Kham.

Which brings me back to travel—the money.

In travel publishing there has been considerable interest in this area. Some paymasters see it as a way of generating content far cheaper (if not for free), and more tailored to a specific audience. Who needs whining human travel writers you need to pay living (or not) wages to, when AI will do it for near-free? To that I’ll quote what the Hanoi travel agent said to me the other day when I asked about two wildly different-priced Hạ Long Bay trips:

“You get what you pay for.”

Note, they all say this—and it drives me nuts.

Money aside, AI is only as good as its diet. So if that diet is predominantly “the top ten things to do in Luang Prabang,” chances are when you ask AI what to do in Luang Prabang, you’ll get that same list.

Stuff like transport and prices is handled, though it doesn’t note that catching a non-stop bus to Hanoi, while possible, is madness.

Back to Michael Running Wolf, in the same interview describing how AI “works” he says:

“The issue with AI is, it is not generating new content, it is actually a façade, these AIs are stochastic parrots, ... so they’re essentially just a statistical parrot, they see data and they’re really good at replicating it, at will, and it is only able to replicate what it sees, they’re not actually able to synthesise new information, ... they’re doing a really good job of seeming like humans to generate say new art, and every pixel that is being generated by these image AIs originates in a previously seen artwork.”

Before going on to say:

“It’s a pretend intelligence”

As with all travel writing, listicles feeding overtourism is a known area of concern, and I’m not sure a pretend intelligence is what the doctor ordered. Travellers need more deliberate guidance, writing that is informed by issues like better empowerment for local people, sustainability, reducing overtourism and protecting the environment.

These issues, AI doesn’t appear to handle well. When I asked it for the “best things to do in Luang Prabang” it gave me a boilerplate list. That it included “Take a tuk-tuk to the nearby town of Vang Vieng and explore its natural beauty,” was pretty funny. Then I asked it “what are the best things to do in Luang Prabang for a sustainable traveller?” and the list, still boiler plate, was largely the same—though the tuk tuk ride was gone. I’m not seeing the intelligence here.

When AI-created listicle websites start popping up daily, what sort of self-referential cycle will begin when robot readers scan robot writers? The situation is bad enough without thousands of new players writing the same top ten lists. Google Search may already be close to broken and this isn’t going to help matters. Some sites, StackExchange most famously, have already banned AI-written responses. Will Google do the same to AI-generated websites and stories? How will they distinguish between a bad writer and a good robot? How can you? Should you need to? Will publishers admit to using AI content? Should they?

All together now. You could generate one of these a minute and have a world guide in no time. Good luck Google.

To a point the consent cat is already out of the bag, but then the next thing is the credit cat. Where was the information sourced from? AI doesn’t give up its sources. When it comes to travel writing, knowing who the author is can be a vital bit of information—at least for me anyway. To my mind, the source is everything, to others, not so much. Theft? Not a big deal for some.

Christian Watts is the founder of Magpie, a CMS thing for tour companies. On Twitter, he declared he was “going all-in on incorporating ChatGPT throughout Magpie.” Yet, when a friend of mine specifically quizzed him about the possibility that some of that material would be lifted from Travelfish, and asked if that was stealing, he wasn’t fussed.

“The way I think about it: If it deems a source worthy, its already trained on it. Every wikipedia page, every lonely planet page etc. When it generates content, it's using its collective knowledge - never specific sources, always unique, so you'll never know. Stealing? probably.”

Always refreshing to see a founder having no qualms about using possibly stolen content in their product.

It’s worth noting in this though, Watts’ use of the term “collective knowledge” and assigning it to AI. It is anything but. Rather, it is humanity’s collective knowledge, co-opted without a penny paid, by the likes of Musk and Thiel who in turn will possibly make more than a single truckload of dosh out of the affair.

Takes a breath.

All service travel writing, to a point is derivative, and there is little writing (in English) about places not written about before. I read widely and I’d be lying to say what I read elsewhere doesn’t influence where I visit and what I write about. Most travel writers have their own take, they add their own nuance to whatever it is they’re approaching. They write for their readership, something that differs from publication to publication. AI strips out the nuance and the humanity—though you can prompt it to add its take on humanity back in. AI produces the sort of travel guide I’d imagine IKEA would write—albeit with clearer directions.

You need a travel guide for pirates? Can.

I took a random paragraph I wrote for Travelfish and ran it through the same tool I put the train site through. The irony of having a robot check if I was a robot wasn’t lost on me, but I was reassured when I was told:

“Your text is likely to be written entirely by a human.”

I don’t plan to change that approach, and I thinks others do at their peril.

Couchfish is 100 per cent independent and reader-supported. If you’re not already a subscriber, and you’d like to show your support, become a paying subscriber today for just US$7 per month—you can find out more about Couchfish here—or simply share this story with a friend.

Don’t forget, you can find the free podcasts on Apple, Pocket Casts and Spotify as well as right here on Couchfish.