Note: Our exisiting coverage for Cửa Đại and An Bàng on Travelfish which were researched and written in 2017 serve as good counterpoints to the following piece as they illustrate now much has changed in just a few years. I’ll be updating them to bring them in line with the following in the coming days.

Let me start by saying I’ve seen more than my share of great beaches. The flip-side of this is I’ve also seen my share of not so great, dare I say, awful, beaches. A product of travelling in circles in Southeast Asia for the last thirty years is that I’ve seen many a beach shift from the former to the latter. Few—if any, move in the opposite direction.

Despite this downwards shift, beaches remain one of the major calling cards for many a Southeast Asian destination. There’s the palm trees, the blue skies, the powdery sand, the warm and lapping turquoise water. You get my drift right?

What we need is a “no building” sign. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

I’ve written before about the perils that rising sea levels hold for the not too distant future. Yet, tourists’ favourite holiday spots washing away are the least of the concerns. The economic and social ramifications of a vanishing coastline will be as vast as the ocean that submerges them. Yes, the calamities associated with this are down the tube a bit—give it another twenty years give or take.

Yet, in some spots you don’t need to wait twenty years. For those who want front seats on the calamity, come to Vietnam. To An Bàng and Cửa Đại beaches, a short bike ride from tourist hub Hội An. I made the trip today to save you the bother, and the beach is an unmitigated disaster area.

What could go wrong? Photo: Stuart McDonald.

First a brief history.

I first visited Hội An’s beach strip in 1993 or 1994. As best I remember, at the time there was nothing tourist-facing on An Bàng, and Cửa Đại had three hotels—the Victoria and two others. The beach, still quite duney in places, went and went and went. To the south, the (then with no dams) Thu Bồn river emptied out to sea, while offshore, the Chàm Islands glimmered. You could walk all the way to Đà Nẵng’s Mỹ Khê Beach and see barely any construction whatsoever. I did it—once. Yes, 1993 was a lifetime ago.

Vietnam’s coast around Hội An catches a bit of weather in October-ish most years when tropical cyclones blow in. While the town often floods and has for decades, the beach districts bear the brunt of it. People die. For the rest of the year, thanks to current, wind cycles and the Thu Bồn, the sand returns—ready to get sucked away again. This combination of islands, estuary and storms create a complex and unique system. Still, this cycle of erosion and accretion (when the sand returns) has been going on forever. Well, almost.

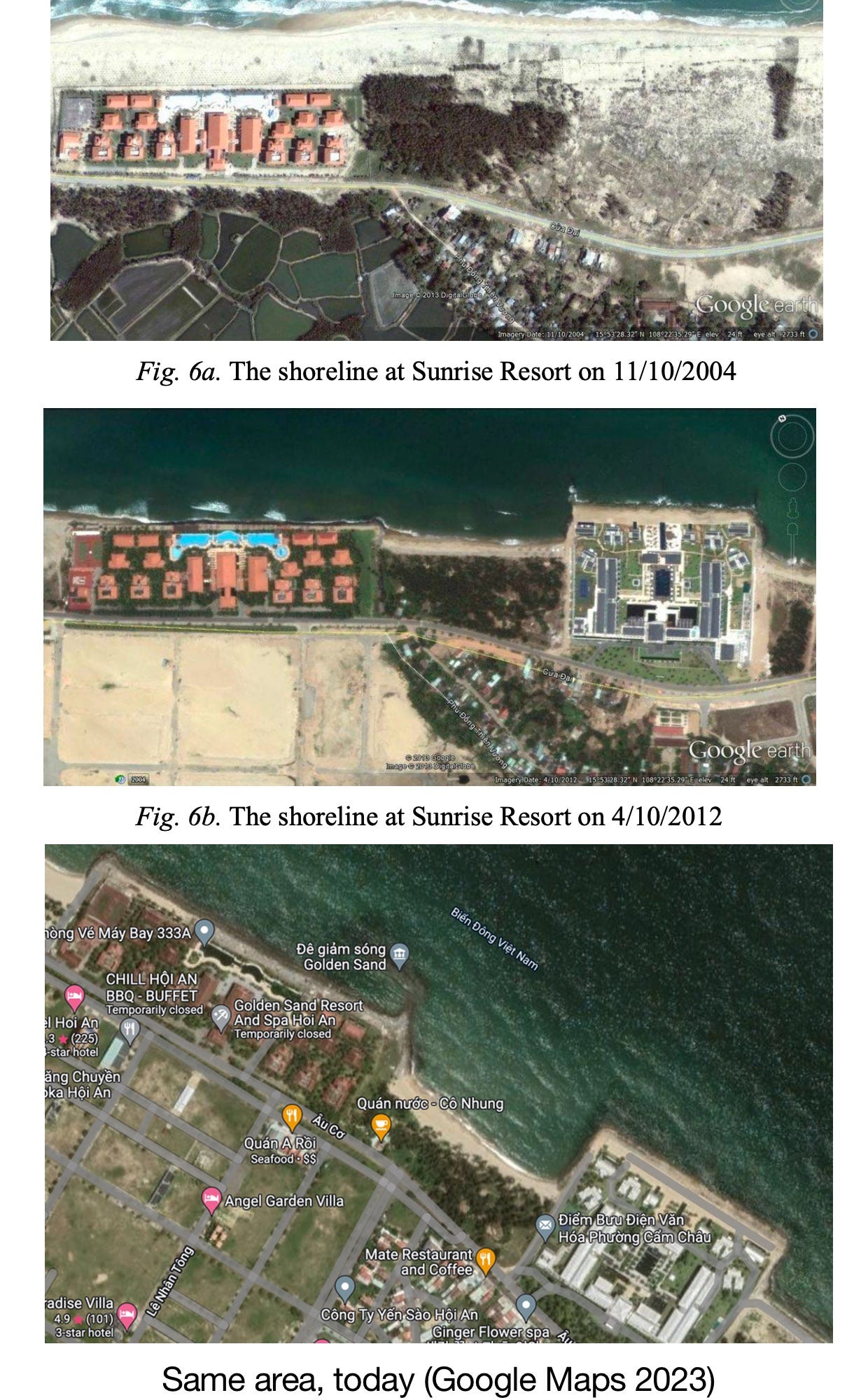

What a difference 19 years makes. First two images (source), third image, Stuart McDonald, via Google Maps.

In recent decades, An Bàng, and Cửa Đại have boomed—a search on AirBnb for “An Bàng” delivers results for hundreds of “homes.” Many sit on what was once the sand dunes that formed a natural protective element for the beach. Off beach meanwhile, at least seven dams now sit on the Thu Bồn. Illegal sand dredging on the river is rife. In a few short decades, a system that has worked forever and a day has started to malfunction. The cycle of erosion and accretion isn’t what it used to be. Add to this, a worsening of the storm cells that hit the region each year, and none of the news is good.

But wait, there’s more!

At the southern end of Cửa Đại Beach, where the Victoria was once the southern-most resort, more resorts went in. Built within metres of the high tide mark, it should come as a surprise to nobody that they started to wash away. At the southernmost tip, everyone’s favourite enviro-vandal Vin Group dropped in the VinPearl Hoi An Resort. Built at the cusp of the Thu Bồn’s mouth, even by Vin Group standards, this was an epic brain fart. Work started on it in 2004, and when the beach washed away, they lined the resort’s periphery with boulders. Writes Do et al:

“Starting from Cua Dai Inlet and going along the beach toward the north, the first resort is Vinpearl Hoi An. The construction started around 2004. After the construction, the shoreline significantly retreated so that the investors chose to protect their resort by construction of a seawall in front of the resort.”

Reminds me of Bali. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

As elsewhere in the world, doing this changed how sand moved along the coast. Other, equally ahhh poorly-placed resorts, seeing “their” beach vanish, did the same. This wasn’t a coordinated response of course, so each wall was in a different style and in a different position. Giant black sand-filled socks dive into the ocean in front of some prime real estate.

The socks appear to be a part of a greater plan to turn the beach into a giant sandpit. This story covers it, along with an interesting video. Set about 250 metres offshore an underwater dyke is being built which will in theory protect the beach. Other reports note the area between the dyke and the beach will be backfilled with sand dredged from the Thu Bồn, which seems ... unwise. Past similar projects, costing millions of dollars, have failed. Similar beach nourishment exercises elsewhere have found the costs to be immense.

The have and have nots. Note the difference in the level of the sand. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

While the beaches to the far south are already gone, up the beach, at An Bàng, the hammer has fallen big time. An Bàng you see, straddles a higher dune than down the bottom of the beach, so while the development is lower key, the fall to the sea is greater. When I walked down the beach today, some places had sheer drops of three to four metres. Take my word for it, the fall is precipitous in places.

Traditionally a more affordable strip, An Bàng is often portrayed as some sort of bohemian whatever. There’s chic cafes and plenty of thatch roofing, distressed wood and washed out whitewash. Members of the informal economy (sorry I mean global nomads) ponder life on their MacBooks. Despite this deliberate rustic-ness, there’s a tonne of money turning over. Shabby chic (and often foreign-owned) joints on Airbnb pass for hundreds of dollars a night.

Watch that last step. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

An Bàng seemed to lack the deep pockets of the grander resorts that made the mess in the first place. Instead, over the years a range of efforts have been made to try to protect the dune. Sandbags failed, as did bigger ones. Even bigger ones also failed. Staggered walls made of bamboo poles, some built atop the failed efforts of earlier years. Sand-filled bags buttress the bamboo, but when the bags fall apart only the spiky bamboo walls remain. These are ideal for catching trash—including the remnants of the bags—it is as unsightly as it is dangerous. Fall on one of those fences after a night on Huda Beer and you will know all about it.

Meanwhile hotels, cafes, and houses continue to wash away. Bathrooms seem resilient, ridge-top solitary loos lord it over the sand, waiting to topple. Elsewhere, half collapsed rooms die a slow-motion death, cement detritus lining the beach. These are, in a way, the worst bit of the entire shit sandwich. If authorities had a modicum of concern for beachgoer safety, it would identify these and remove them before they fell into the sea.

It is, truly awful.

I’ve run out of metaphors. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

So what should happen?

The Vinpearl should absolutely be levelled. Others that likewise rely on the walls that exacerbated this mess should go too. I’d stretch this north to the Marriott (according to Google Maps) garbage fire under construction, and Palm Garden. In their place, aggressive regeneration to return the dunes to their natural state needs to begin.

Up An Bàng way, anything on the cusp of the ever-growing cliff remains in a danger zone. These places haven’t made the mess in the way the southern joints have, and over time, they may be a little more tenable. Hard to say.

Is anyone awake at Hội An Tourism? Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Will any of this happen? No. It was suggested to me that local authorities will continue to affix bandaids while the connected firms that made this the mess it is continue to make money hand-over-fist. As a Vietnamese tourism insider put it to me, “our government prefers to half fix things so they can half fix them next year and the year after. There’s more money for everyone that way.”

Instead, the storms and floods will continue to get worse, as will the erosion. More places will fall into the ocean, littering the beach with chunks of smashed toilets and bathroom walls. People will continue to lose their livelihood. At some stage, when enough of the beach has gone, people will stop coming.

The biggest outrage? What I was charged for this coconut. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Cửa Đại and An Bàng are the canary in the coal mine for the region. Other countries need to wake up and see what is coming and start planning today—not in twenty years.

Couchfish is 100 per cent independent and reader-supported. If you’re not already a subscriber, and you’d like to show your support, become a paying subscriber today for just US$7 per month—you can find out more about Couchfish here—or simply share this story with a friend.

Don’t forget, you can find the free podcasts on Apple, Pocket Casts and Spotify as well as right here on Couchfish.

Share this post