Travel writing, at least in the travel guide niche is a bit akin to being something between a soldier and an archivist.

Big skies north of Bima, Sumbawa. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Visits demand military planning. A method of approach to allow the writer to take in as much as possible in a minimum of time. Everything filed, for me in notebooks and a smartphone. Later it all gets regurgitated—hopefully into a state that makes some sense to the traveller.

Seeing everything but experiencing nothing

There’s the accommodation and sights, but also transportation and food. Is there a tourist office or police station? Where are they? Do they speak English? What days and hours are they open? Is there an English menu? What is the latitude and longitude? Do they have WiFi? Does it actually work? What is the password?

Years ago I read a piece by a travel writer working for a legacy publisher. The story has been lost to the interweb ethers, but there was a poignant moment that will always be with me.

Lost near Sape—at least there were signs. Sumbawa. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Overcome with the vast array of information demanded, they sat on the bank of some gigantic muddy river in China, and cried.

To this, I’d add there can also be a friction with people. Why are you asking me this? Why do you want to know what time every bus goes to everywhere? Who are you? No more questions. Please.

A travel writer friend once described this gig as “seeing everything but experiencing nothing.” There’s a lot of truth to this. With military–grade planning you can factor in a loose day under a waterfall, but that day means a day lost elsewhere. Lingering has a cost—the piper must be paid.

Lining up ducks

Planning is a vital part of the process—at least if you want to emerge at the other end with change in your pocket. A few strands of sanity at the end are also welcome. As with travel itself, there is no right way to plan a travel writing trip, but one must plan. All have their own approach, and often one which varies with the terrain. Islands and beaches present different challenges to capital cities.

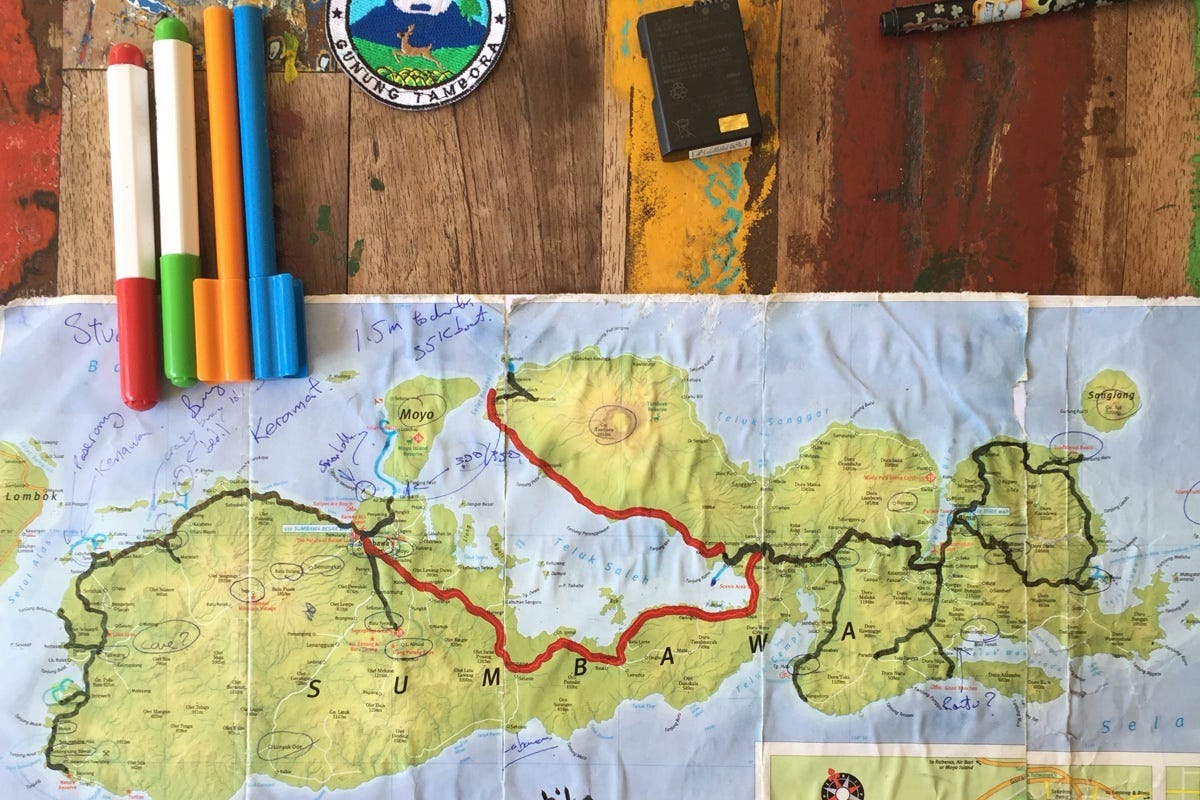

Paper maps are useful. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

I start with a paper map. I mark on it a rough itinerary, places worth more time than others. Possible day trips and overnighters off the main track. From there I go to notebooks, a page to a place, listing out my best hoped for result. Ideal world and all that. Will the bus from K to L breakdown? Will a bridge be washed out? Will the ferry sink or the flight be cancelled? You can line your ducks up in a row, but rare is the trip where all the ducks stay in place.

Depending on the destination I may find some books to read—a literary hook always fits for a hanger. I’ll also collate a list of people I know (or know of) and grill them for information. If our timelines dovetail, I’ll meet with them—more lost time, but sometimes terrific finds.

The most patient hotelier ever, in Alas, Sumbawa. His parting words: “Mengapa kamu di sini?” (why are you here?) Also, it there was ever a town with a fitting name, it is Alas. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

I’ll also spend a good amount of time on, of all things, Instagram. For all the fakery and whining, it remains a solid resource for what stuff looks like. I’ve also found it a great reservoir for local talent.

Local talent

First, some definitions.

What do I mean when I write “local”? I mean someone who is from there—perhaps not born in the destination, but certainly from the country. Foreigners living in country can also be a terrific information source of course, but, like locals, can be hit and miss. It depends on what I am after. Are you after a listing of expat bars? Or are you after an expat with the lingo and terrific community connections. Both have their uses.

Chance of me finding this buffalo race outside of Sumbawa Besar by myself? Zero. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

By “local talent” I mean local travel evangelists. I don’t mean travel agents (who I try to avoid as much as possible), but rather people who are just “into where they live”. I try to meet up and if we’re on the same page, I’ll hire them for a few days to show me around.

It works pretty well. They want to showcase where they live and I need to know what is worth seeing. Where do they think is great, where do they eat, which hotels do they recommend to friends and so on. It is a great way to surface things I would not have found otherwise. Of course not all are hits—splitting the hits from the misses is my job (well, one of my jobs). I’m the filter.

Floresians on Easter break. Resort had beer, so passed my filter. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

As much as you might think people from everywhere are into the same stuff, in real life it doesn’t work this way. In Ipoh for example, a guide took me somewhere I’d never recommend to anyone, ever. Ever. He loved it though, and was baffled why I hated it. Likewise with food. It is all well and good to promote local eateries, but I’m not going to list the brothel one guide took me to for lunch—even if the noodles were great.

Despite the few clangers, most of what they unearth veers between solid to amazing. Some I could have found by myself—eventually—but more often than not I wouldn’t have. When your guide has lived in the town all their life and you have 48 hours there, you’re at a slight disadvantage.

Local knowledge

One story I like to tell was when I was in a semi–remote area of eastern Indonesia. I’d hired a guide for four or five days, he’d arranged for me to borrow a friend’s scooter, and we rode all over the joint. It was fantastic.

We don’t get many of your kind here. Sumbawa Besar. Photo: Their mate.

At one stage we reached a junction in the road—another travel writer had told me the road to the left was safe. My guide said it wasn’t. The right turn though meant over a day of riding to reach our intended destination. I argued for the left, and he gave in, but wasn’t happy about it.

A while later we pulled up for gas and the attendant asked where we were going. When I said the name of the town, he did a double take and turned to my guide. They spoke too fast for me to follow, but the meaning was pretty clear from the old guy’s body language. The guide turned to me and said:

“He said the road is not safe. He would never take his family that way.”

That was good enough for me. We turned back and went the other way.

New peak, new friends. Atop Tambora, Sumbawa. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

On the upside, at the town we overnighted at, my guide had a friend there, another Instagram evangelist. We got in touch and she took us on a great half day tour through some spots I would have never ever have found otherwise. Glass half full and all that.

Sights and safety, food as well. All is super useful local knowledge that I’m able to filter into the guide. It is though, a shame few locals write for international travel guides on their own countries. I have a post on this subject which has been smouldering away for the last month, but it is a complicated case. Plenty of food for thought.

Perhaps related to this, an interesting side–point. In almost all cases, when I’ve asked the guide would they like a credit for their assist, the answer has been an emphatic no. They’re happy though for me to pass their contact details on to other travel writers (which I do). In my experience, they’re not in it for fame—the money is welcome though!

Take the leap. My guide showing how it is done, near Merente, Sumbawa. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Instead, they’re after the pleasure of showing someone around places they love. Funnily enough, that is the same reason we started Travelfish.

And I reckon that is pretty cool.

Have you had a good local guide? Add your tale to the comments below!