Readers may recall a piece I wrote in July about when we offered our daughter as a bribe to an immigration officer. No? You can read it here. At the time we were on our way to Kep for a wedding, and while the wedding was the main reason, close behind was the fresh crab.

Crab shacks. Photo: Mark Ord.

At the time, Kep’s fresh crab scene was a shadow of what it is today. Little more than a collection of wooden shacks, the setting was low slung tables and hammocks. The crabs, trapped in the sea grass fields right offshore, were as fresh as fresh gets—and not a first date meal.

Fast forward to today, and the story is not so sanguine. The offshore sea grass fields may well be ideal breeding grounds for crabs, but also for many other species. Illegal fishing has damaged the fields—and the reefs further out. Even without that, the increase in demand has proven to be unsustainable. Today, more often than not, your crab is from over the border in Vietnam. As one crab vendor says in this piece:

‘Vietnam,’ she explained. ‘You can’t get crabs this size in Kep’s waters anymore.’

Tourism eating itself (and the crab) yet again.

More than just crab on offer. Photo: Nicky Sullivan.

The wedding guests are all put up at the well flash Knai Bang Chatt. It is a wonderful example of the architecture I touched on in this earlier piece about Kep. After lunch at the crab market we return to the hotel for some lazing around time.

The property is expansive with a tree–lined lawn garden running right to the water’s edge. A wooden platform, part of what will become the hotel’s “sailing club”, juts into the sea. With a couple of lazy chairs dotted around, it is the perfect spot to spend the late afternoon. I lose time, reading and watching a catamaran becalmed offshore.

Before the volley–boy and elephant. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

Behind me, centred on the lawn, a horizon pool beckons and a bunch of guests are cooling off before dinner. A mix of mostly male expats and Khmers working for acronyms in Phnom Penh, I don’t know many, but the pool swings the deal.

The water is that wonderful tropical tepid, the slightest chill as you slip in, but somnolence comes fast. A young boy, the child of one of the expats joins the crowd, and they start playing volleyball with him—and I mean with him. He’s the ball as they pick him up and throw him from one end to the other.

This job kills me I tell ya. Photo: Samantha Brown.

The racket is annoying—the scene is so peaceful, the sailboat still loiters in the very late light. I move off to a corner of the pool and watch from afar. The boy is enjoying it (I think!) and one of the men, an American military contractor, has the strength to throw him almost the length of the pool. It is impressive and scary in the same breath.

I roll over to watch the sun set and as I do, an elephant slowly walks past me on the lawn. Led by its mahout, it trundles by, oblivious to the shenanigans in the water. The elephant had a role in the ceremony earlier in the day, so it isn’t totally out of the blue, but still, it adds to a magical, other worldly scene.

Last light. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

The next morning, up early thanks to Lyla being still so very young, I take her to sit in a garden sala at dawn. The grounds deserted, we laze around till eventually another guest, A, also with a young child joins us.

She’s an American, like many of the guests, working for an acronym in Phnom Penh. I know her, but only vaguely, and I ask about her work. Her field is about as far removed from the other worldly scene at Knai Bang Chatt as you can get. Bauk. A Khmer word, bauk translates as “plus”, but in this case, it refers to gang rape.

Repeated surveys have found that many Khmer men find the practise acceptable. Writes the Guardian in 2003:

“Gang rape is now one of the most popular after-dark pastimes among the affluent, unmarried 20-30 something males of the country’s larger towns.”

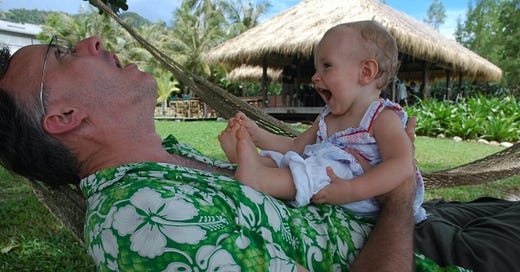

Lyla and I having a laugh about the time we offered her as a bribe to immigration. Photo: Samantha Brown.

A tells me how her work involves Khmer sex workers, who bear the brunt of it, but also those outside sex work. She tells me of the abuse, but also how it has been so normalised in male Khmer behaviour.

Her stories are beyond horrifying and I’m ashamed to have never heard about it before. She asks if I can speak Khmer, when I say no, she says that’s a shame, as if I did I could ask our night security back at the house about it.

“You wouldn’t like their answers,” she says, “It is everywhere.”

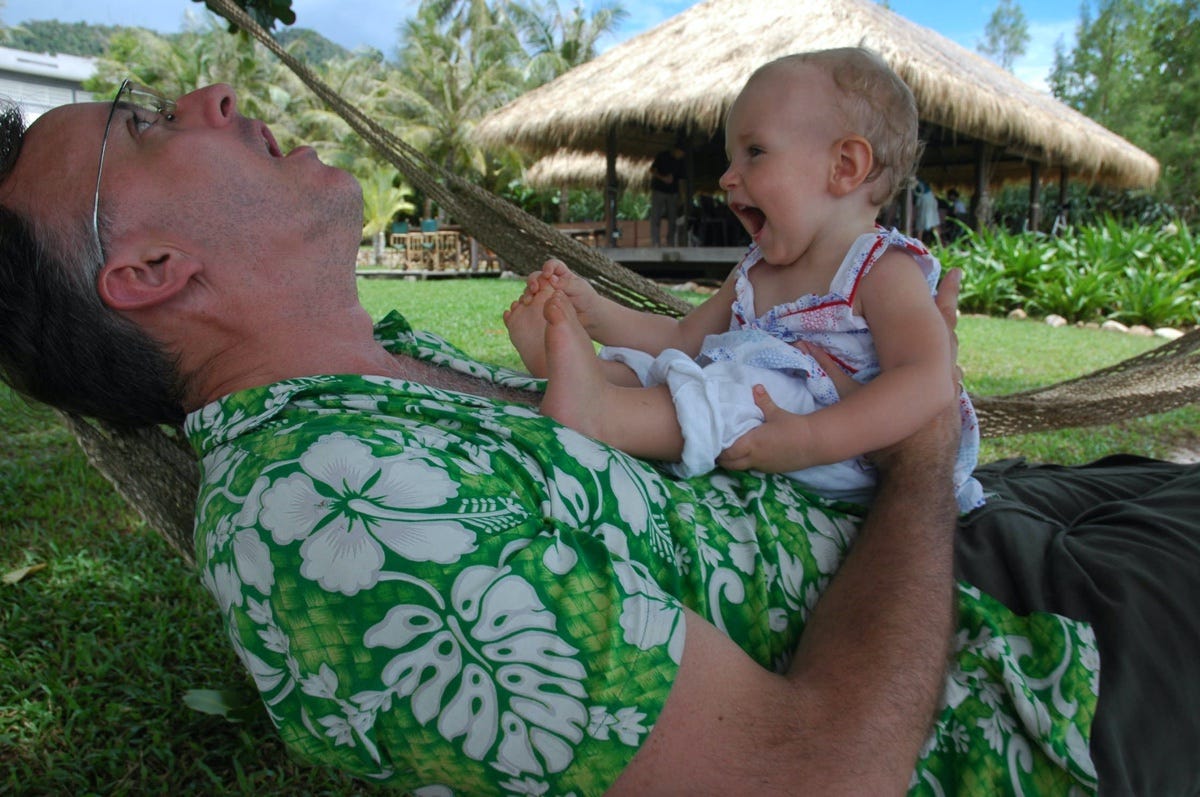

Lyla was thankfully oblivious to the conversation. Photo: Stuart McDonald.

A waiter walks over and asks if we’d like coffee, we both do. When it comes, we sit on the edge of the sala in silence, the two kids playing on the trimmed lawn in front of us. First light smears out across the Gulf of Thailand.

Tomorrow: Off to Rabbit Island.

Share this post